Perhaps the best way to start is to acknowledge a little anachronism, just for everyone keeping track: technically, the collection titled Little Wizard Stories of Oz wasn’t published until 1914, after our next novel, The Patchwork Girl of Oz. However, the individual Little Wizard Stories were published on their own before the novel, in 1913. So here we are, and here we’ll stay, and that’s allllllll that’s left of . . . wait, wrong reference.

Perhaps the best way to start is to acknowledge a little anachronism, just for everyone keeping track: technically, the collection titled Little Wizard Stories of Oz wasn’t published until 1914, after our next novel, The Patchwork Girl of Oz. However, the individual Little Wizard Stories were published on their own before the novel, in 1913. So here we are, and here we’ll stay, and that’s allllllll that’s left of . . . wait, wrong reference.

Basically, the Little Wizard Stories exist to remind the public that Oz exists – as if they could forget! – as well as to drum up anticipation for Patchwork Girl. In that regard, they are not at all dissimilar to one of Baum’s commercial undertakings from almost a decade earlier. Queer Visitors from the Marvelous Land Of Oz was a full-page, syndicated newspaper comic strip – as was common in those days, each installment illustrating a small text story with separate “funny” pictures – that ran from August 1904 to February 1905. The tiny Ozian adventures were meant to promote The Marvelous Land of Oz over the holiday season (it having been published in July of that year). Baffled? Well, we were, too.

These two sets of tiny little stories may be confusing, but thankfully, they’re also really short – so why not read a few before you start our blog? Here are online versions of Little Wizard Stories of Oz and (the text of) Queer Visitors from the Marvelous Land of Oz. And now, without further bewilderment . . . .

So, Nick, says Sarah, let’s talk about these horrible little stories.

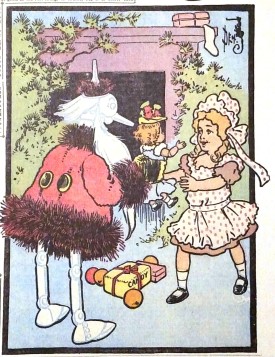

Must we? asks Nick. (Yes, that’s him in the picture.) We’ve been reading these novels month to month and looking at Oz pretty much exclusively as it “unfolds.” We didn’t have the opportunity to go to a staging of the 1902 Wizard Of Oz, which I now realize was a big part of “Oz the Idea,” but here we are with what feels like a moment of brand awareness with Little Wizard Stories. For the first time in this blog, we are experiencing Oz outside of the novels, seeing it repurposed, and it’s just not as enjoyable, is it?

Must we? asks Nick. (Yes, that’s him in the picture.) We’ve been reading these novels month to month and looking at Oz pretty much exclusively as it “unfolds.” We didn’t have the opportunity to go to a staging of the 1902 Wizard Of Oz, which I now realize was a big part of “Oz the Idea,” but here we are with what feels like a moment of brand awareness with Little Wizard Stories. For the first time in this blog, we are experiencing Oz outside of the novels, seeing it repurposed, and it’s just not as enjoyable, is it?

Not at all. These stories are what I would call, in media-speak, a “soft reboot” of Oz. Their goal is to reintroduce and reestablish old characters, not just in a new Oz novel but in a continuing series of novels from here on out. It is, as you say, an exercise in branding, and that’s not a bad thing, per se. The problem is that Baum doesn’t remember to give the characters any characterization, and in writing them into little stories, he doesn’t actually provide much incident. There’s not a lot to work with here, is there?

No, and there’s not much directed to Baum’s established readership, either. Baum very rarely gives us a continuing story of Oz, but often, I think, he at least tries to appeal to kids who read the previous books. This feels aimed at a very different readership: a younger and more picture-oriented one. You could see that readership being addressed in the earlier books because they were so visually rich. You and I are unlikely to enjoy these new stories because they are, to an extent, promotional . . . .

They’re completely promotional. They were priced at 15 cents each, which tells you a lot, because an equivalent novel-length Oz book of the time was $1.25. That’s a jump, isn’t it? All six of these stories cost less than one novel.

Wow.

Something that’s hard for me is that I’ve known about these stories so long – since I was very, very small and had a paperback that reproduced the pictures in black and white – that it’s hard for me to recategorize them within their original context. I struggle to view them purely as promotion, although that’s precisely what they are (and really, I would argue, very little more). I don’t think I’m alone there. They’ve taken on an additional weight in hindsight, mostly for two reasons: because they were later collected and compiled as a book – Little Wizard Stories of Oz – and because Neill illustrated them. That gives them a certain hint of legitimacy that makes them hard to ignore. On the other hand, we’ve almost completely forgotten A Day in Oz, the play that Ruth Plumly Thompson wrote for department store promotional events; it was never published in book form and Neill didn’t illustrate it! Yet it essentially performed the same function of publicizing new Oz books.

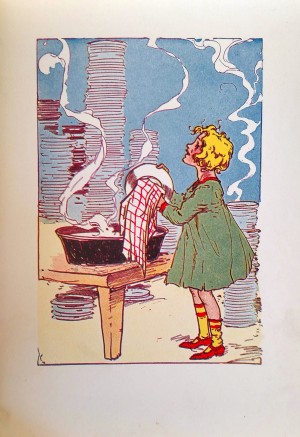

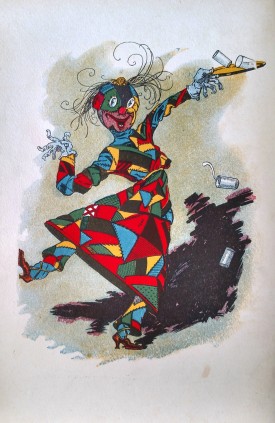

And to the extent that we enjoy the Oz books because of familiar elements – because they’re books, specifically, and books formed in part by Neill’s contributions – there’s quite a lot to like here, because Neill’s work is generally very strong (albeit with some weird lapses). It’s not his best work, but a lot of it’s very attractive.

I’d say it would be even more attractive if it wasn’t colored. The colors here are often very garish; sometimes that really works, but sometimes it doesn’t. That’s even more affected by the quality of the reprints modern fans are used to reading; we’ll discuss that more in a minute.

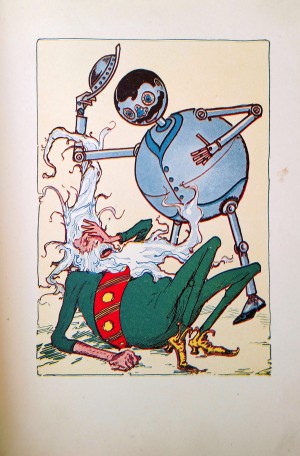

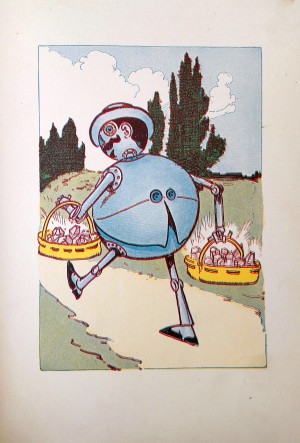

Mm. Tik-Tok is, for some reason, blue.

We’ll come back to that, I promise.

I brought up the “rebranding” because if these had sold really well, and Patchwork Girl hadn’t, I can imagine these being the new format for the Oz books. I don’t see Baum being massively wedded to Oz as a series of novels. It feels like, here, they’re testing out exactly who the readership are and what will people will buy. Perhaps there’s a parallel world with seven Oz novels, followed by a decade of picture books with these caricatures of our favorite Ozzy friends.

Misogyny, Fishing, and Buttons

Well, let’s talk about our favorite Ozzy friends. Are you at all intrigued by the characters he chose to highlight in these stories? I am, slightly.

It’s interesting. I think all but Dorothy and Ozma are men –

That’s not a huge shock, surely.

Well, there’s no Polychrome, whom he seemed to have been getting quite into – or Glinda, obviously. And no Billina!

That’s true.

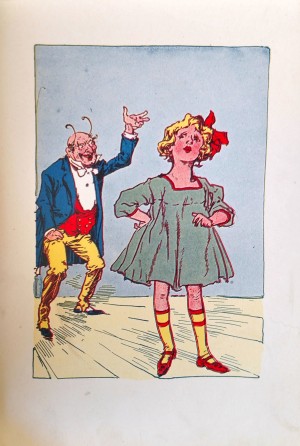

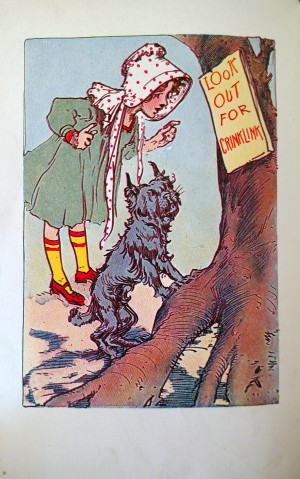

The girls don’t come out of it particularly well, either. Little Dorothy and Toto is a slightly misogynistic little fable, I think.

You’re not wrong. To me, that’s the least of the six Little Wizard stories – by some margin.

That’s not saying very much, really.

No. In fairness, we know for a fact that Little Dorothy and Toto does not have the original ending Baum intended. In the published version Toto comes close to killing Crinklink while in his tiny form, but in the original draft, snap! No more Crinklink.

Oh! Who changed it?

Sumner Britton, of Baum’s publisher, Reilly & Britton. The Book Collector’s Guide to L. Frank Baum and Oz has a nice quote about it, from one of Britton’s letters: “Toto kills Crinklink on much the same order as a terrier would kill a rat and thus everybody gets away all right. This is clearly away from your usual style of not doing any killing.” It was Britton’s suggestion that Crinklink reveal himself to be the Wizard in disguise to teach Dorothy a lesson, which is a terrible ending.

Yeah. Everything about that is pretty dreadful, not least because it seems to go against one of Baum’s major themes of pioneering girls setting forth on adventures! It undermines that completely.

It does. There’s a bit at the beginning where Dorothy makes a point of telling Toto, “If I get into trouble you must take care of me,” which is clear foreshadowing for the original conclusion – so it’s obvious Baum’s edit to attach a new ending wasn’t especially intricate.

Isn’t it interesting the publisher was giving such heavy editorial guidance, when that’s one of the major things we’ve been talking about – the absence of that in previous books.

Maybe they’d finally got wise after Sky Island’s patching machine. My guess is that Baum didn’t care terribly much whether he was undermined or not: he just wanted these to sell in the shops.

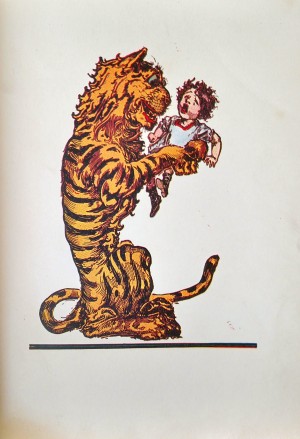

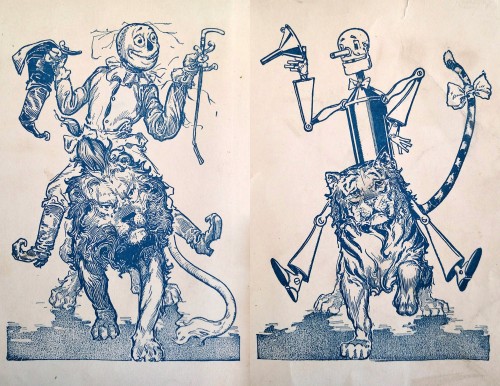

I actually liked The Cowardly Lion and the Hungry Tiger – to an extent. I liked it as much as I liked Baum’s fairy tales in The Magical Monarch of Mo. It’s kind of a fable, and it almost makes you laugh – but it would be horribly inappropriate to read to a small child now, and may well have been even then! There are all sorts of typical references to extreme violence and gags about death delivered by our favorite characters.

With a smile, though – that’s the odd thing. It’s all meant to be terribly funny, I think.

In reality, it’s kind of crude.

In all the various reprints of these stories down the line – as booklets, as jigsaw puzzles, as strange oversized British books – it seems like whenever they needed to cut two of the stories, these were the two to go. That’s a little odd. You’d think they’d try, above all else, to keep a story with Dorothy and Toto – the most audience-familiar characters – in the title. I wonder if someone saw these as the weaker of the stories. It might have been Britton. It might even have been Baum himself.

At least The Cowardly Lion and the Hungry Tiger has the structure of a very, very short fable. Something like The Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman is like a little Silly Symphony cartoon short. “There lived in the land of Oz two queerly made men who were the best of friends.” That’s a good opening, isn’t it? It’s like you and me!

It is! And it’s a very Baumian opening. “They were so much happier when together that they were seldom apart; yet they liked to separate, once in a while, that they might enjoy the pleasure of meeting again.” He liked that kind of thing – simple, folksy philosophy.

Really, the story is just about two funny-looking people getting into trouble on a fishing trip!

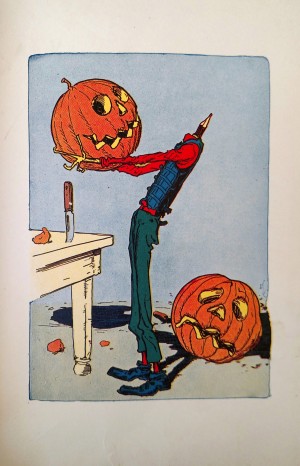

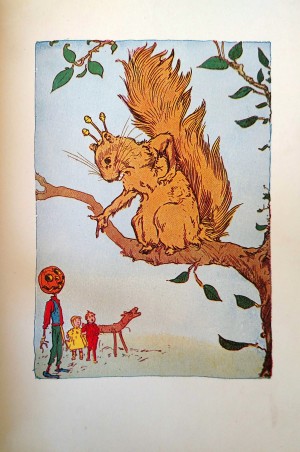

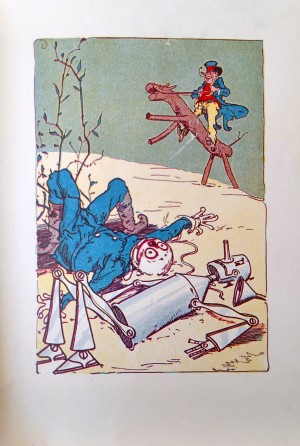

Yup. There’s not really much to it, and there’s not much to Jack Pumpkinhead and the Sawhorse, either.

I can’t even remember what happens in that one, and I’ve only just read it.

Both stories are about our heroes having accidents and needing to be saved by the Wizard. There’s no real plot, just a singular incident, and there’s not much characterization, either, although I do like that Baum has created evil squirrels and well-meaning if slightly cranky crows. Neill has, of course, illustrated them accordingly. If it wasn’t for Neill’s pictures, I’m not sure where we would be.

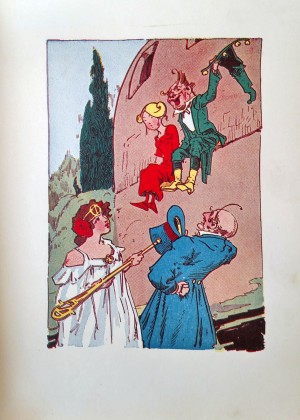

There’s Ozma and the Little Wizard, where Ozma seems to be fairly ineffectual.

. . . And the Wizard has an obsession with enchanted buttons. Think about it.

Oh yes, that’s true! That’s . . . a bit weird. Funny that Baum would repeat that element in two stories. It does feel very fairy tale-ish, though. The bit with Crinklink’s animal head buttons felt like something authentically weird, so I was really quite keen on that story at that point – but it didn’t last very long.

No, thankfully, nothing about these lasts very long.

Fire Burn, and Clockwork Bubble . . .

If we’re taking the stories in turn, I think Tik-Tok and the Nome King is my favorite, and the only one I would reread.

Me too. I’m a little bit curious why this story even exists, but I think I have an answer – Baum’s play The Tik-Tok Man of Oz would have just been on the stage, and it would have featured both Tik-Tok and the Metal Monarch (as the Nome King is called in the play), so whether or not Baum intended to continue using them in the book series, he saw them as popular and significant enough to use for publicity. If you notice, a large portion of the plot of this one involves the Nome King as a sort of maker of machine parts.

Right. That’s why Tik-Tok goes to him in the first place.

That’s not consistent with his earlier appearances in the books, but it’s consistent with the play. In addition, I could be wrong, but I don’t think Baum ever refers to Tik-Tok as being copper in this story. The only references are to iron and steel, and he’s called a “clockwork man” – again, what he’s frequently called in the play. You asked before why he’s blue – well, I think that’s to signify that he’s metal, but no longer specifically copper. We’ll never see a copper-colored Tik-Tok again; he’s always blue in color plates from here on out, something that utterly befuddled me as a child.

Oh, how interesting to see that influence of other versions of Oz coming back into the books again. It does get very theatrical, I guess, because it’s got a sort of parody of Macbeth, where the Nome King thinks he’s haunted by the ghost of Tik-Tok.

Yeah, I had a suspicion about that. I went and looked, and wouldn’t you know it? Baum liberally adapted the entire plot of this story from Act II of his play. Quelle surprise. Specifically, it’s from a sequence in Ozma of Oz – the play that later became The Tik-Tok Man of Oz – where the Shaggy Man manages to “blow up” Tik-Tok, and he has to be put back together again by the Metal Monarch. Afterwards, the Shaggy Man thinks Tik-Tok has come back to haunt him as a ghost. Sounds familiar, don’t you think?

Very.

We’ll talk more about The Tik-Tok Man of Oz in a couple of months, but I agree with you – it’s a contained little story, and probably the best, although the publisher stuck their oar in again. Apparently, Britton didn’t like the idea of Tik-Tok being a ghost, so he asked Baum to use other language. Again, a great quote from a letter: “This story is bully and full of ginger right from the start . . .”

I’m going to start using that expression. This blog is full of ginger!

Aren’t we all. “. . . And it is a shame to make a suggestion, but we are fearful that the use of the word murder and the term ghost will be considered a grave departure from the regular way of L. Frank Baum and his fairy stories.” Suddenly, they got very worried about the death jokes.

That’s so funny! What Oz books have they been reading? It feels a bit like the modern issues with Harry Potter and anxiety over the supernatural. There are references in these stories to eyes being pecked out and babies being eaten, and yet it’s the idea of a robot coming back as a ghost that troubles these people!

. . . So, um, yay. That’s Little Wizard Stories!

That’s it, isn’t it.

If we want to stretch our analysis out just a little bit, it’s interesting to note that most of the Baum Oz books saw reprints – especially in the 1980s and ’90s, from Books of Wonder – that attempted to very, very nearly reproduce the look and feel of the original editions. Not so Little Wizard Stories of Oz. True, it was reprinted a few different times, but every one significantly altered the presentation. The colors, in particular, have been altered. The easiest thing to notice is the Wizard’s coat, I think; in 1914’s Little Wizard Stories of Oz, it’s a bright, royal blue. In all the reprints I’ve seen – at least, the ones with color pictures – it’s a shade of teal.

Huh!

Tiny little differences like that affect the overall attractiveness of the stories, at least for me. I really like that first, collected 1914 edition. The typeface isn’t too big, and it’s entirely printed in dark blue instead of black, with gorgeous dark blue endpapers of the Scarecrow and Tin Woodman. The little story headers are in dark blue, too. Aesthetically, I find it very pleasant to look at, even if the pictures are sometimes organized in a way that poorly matches the flow of the story.

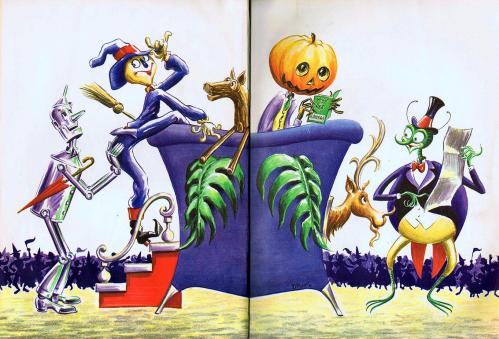

I think the formatting’s really nice in the little 1939 editions we both have, where they’re collected two stories to a book (see photos at the start of the blog). I love the large print. In the Books of Wonder edition, the art’s been reproduced with the lines a bit finer. I quite like the gaudiness of these colors sometimes, where it works, like in the Jack Pumpkinhead pictures. He’s completely made up of big blocks of color himself, isn’t he?

If you look, the major portrait of Jack and the Sawhorse was reused later in The Patchwork Girl of Oz. So was that picture of Dorothy and Toto finding the sign the says “Beware of Crinkilink” – but in the later book, it’s amended to “Beware of Yoop.” Fortunately, on that occasion, it’s not the Wizard in disguise.

You know, the thing that I find interesting about these stories, inasmuch as I find anything interesting about them, is the focus on the Wizard. He’s even in the title, and I assume, again, that’s to do with branding. He’s a completely different character from any depiction we’ve seen before, and I’ve been trying to work out why there’s this new obsession with him, because he’s not a very interesting character. Is it just because the original book is called The Wizard of Oz? It’s really strange.

More so the play, I think. Also, in newspapers at the time, Baum was called things like “The Wizard of Oz Man,” so the title got bandied about a lot. I think it may even be part of why he brought the Wizard back in the first place – but definitely, having brought the little fraud back, it’s why he makes him into a significant character: so he can justify using that name over and over and over! Reilly & Britton had no rights to The Wizard of Oz, but they could use the character – and refer to him – as much as they wanted.

That’s really interesting, because it explains the meaningless title: Little Wizard Stories of Oz.

It does. As a point of comparison, in 1939, Reilly & Lee insisted to Thompson that her book have the words “Wizard of Oz” in the title for marketing purposes, so it became Ozoplaning with the Wizard of Oz. That was directly to take advantage of the publicity surrounding the MGM film, when they couldn’t publish the original book itself.

That’s funny. I feel like it’s something I knew but wasn’t conscious of – the return of, and focus on, the Wizard. He is such an anti-hero in his original appearance, and he’s becoming more powerful and magical as the stories go on; here, he’s got Glinda’s role, basically. He’s the center of everything, and he just keeps popping up and saving the day with his awesome powers!

It just went on, too – even if you look at a book from the ’40s, the list of titles on the jacket flap starts with #1, The Land of Oz. It’s not until 1956 that Reilly & Britton could acknowledge The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, because it finally went into public domain, and they could publish their own edition – and even then, they put it at the top of the list, unnumbered! In the meantime, they’d published cheaper, popular editions of Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz, The Scarecrow of Oz, and The Tin Woodman of Oz, so they’d been able to use those big, familiar characters’ names as publicity without breaking the law.

That’s some real food for thought in terms of how a reader’s perception of Oz might have been shaped by what was available and how it was publicized or disseminated. The Wizard is a major character in these stories, in the same way that there’s so much of the Woggle-Bug in Queer Visitors from the Marvelous Land of Oz, but it’s not because Baum is necessarily interested in them at all. It’s all a sales pitch.

They’re Here, They’re Queer (Get Used to It)

That leads us naturally on to talk about Baum’s other attempt to promote the world of Oz through little tiny stories, Queer Visitors from the Marvelous Land of Oz. I think it’s more than reasonable to discuss these alongside Little Wizard Stories, despite their being almost a decade apart.

That leads us naturally on to talk about Baum’s other attempt to promote the world of Oz through little tiny stories, Queer Visitors from the Marvelous Land of Oz. I think it’s more than reasonable to discuss these alongside Little Wizard Stories, despite their being almost a decade apart.

Absolutely, especially as we’d missed them out before! I hadn’t quite noticed that they should have come earlier.

I admit – I skipped them! I thought to myself, shall I torture Nick with these between Marvelous Land and Ozma? No, I thought, that’s when he ups and leaves the project, never to return . . . .

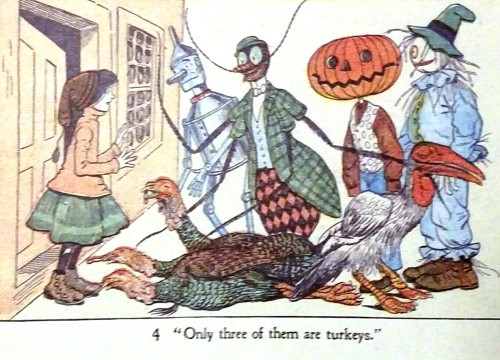

Ha! Well, it’s funny that you say that, because I found them oddly charming. Of course, that’s leaving out the frequent, awful racial stereotypes, and the format, which obliges them to be completely ephemeral nonsense little stories. In comparison with the Little Wizard Stories, which are supposedly promoting and focusing on those characters, here they seem warmer, funnier, and more enjoyable to read.

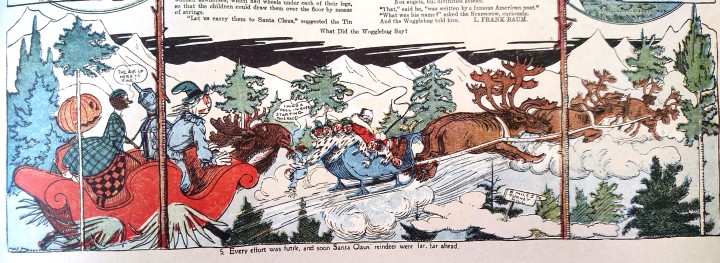

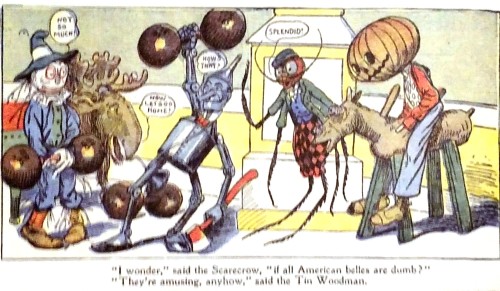

I agree with that – the Queer Visitors stories are quite charming, but in a very specific way. Personally, I find that they need to be surrounded by pictures, as was intended. (Here, thanks to Wikipedia, is a full-page example of one of the original strips.) Whether you’re reading the original, gigantic newspaper pages with Walt McDougall’s art, or you’re looking at the heavily rewritten book adaptation illustrated by Dick Martin, or you’ve even got one of the collections with pictures by Eric Shanower – well, it doesn’t really matter, and it’s not just because they’re all pretty good. The illustrations count for a lot because the stories are almost at the level of having been written on the back of a napkin. That doesn’t mean they’re “bad” stories, necessarily; they’re just very slight. Particularly once Baum gets over “What Did the Woggle-Bug Say?” – his bizarre attempt at ending each story on a trivia question, so readers could send in an answer for prize money – they’re very moralistic.

Yeah. The “What Did the Woggle-Bug Say?” ending manages to drain the last drops of enjoyment you can get out of these. What feels like it’s winding up to a punchline always ends up being a sort of general knowledge quiz. It’s really banal! That’s what I meant about the format: they’re very slight, but also, they just end, in a weird, David Lynch-esque crash-zoom on the wrong thing. Very odd.

More than anything, I like the idea of Queer Visitors – which is to say, I love the idea that Ozma sends all her friends in the Gump as official ambassadors to our world, and they go on a whistle-stop tour of the United States, stopping by Mars and Jupiter along the way, and they have all sorts of adventures and eventually meet Santa Claus. Because . . . why not?

I think the weirdest thing about it is that Baum didn’t rewrite them into a novel, because “the Oz characters come to America” seems like the obvious Oz novel to write. Nobody’s ever done a TV series like this, either, or a graphic novel, and I don’t get why. It’s a collision with so much potential; it’s funny, it’s cute. It’s even more Muppety than the Oz books are.

Oh, it is a very Muppets Take Manhattan concept, isn’t it? There is some great imagery, too. I really love the idea of the Tin Woodman being turned into a giant magnet, and that the Scarecrow can just magick up a car.

There’s a hapless Jack Pumpkinhead as well, and a great bit where they all go off to find a missing child and bring back about thirty of them, which is very funny.

I even like Walt McDougall’s Gump, who – if you look at him – was clearly the inspiration for the Gump’s design in Return to Oz, as opposed to Neill’s. In newspaper page after newspaper page, McDougall’s Gump has speech bubbles that say pathetic little things like, “Is it over yet?” or “Can we go home now?” It’s great. Yeah. The whole strip is a really fun idea.

McDougall, Martin, and More

Staying on McDougall, I really liked his work, actually. It reminded me of how we talked a couple of times about Baum not liking Neill’s work, because it is wasn’t comic enough. I could really see McDougall doing wacky illustrations for the Oz novels, and you know, that working kind of nicely. They would’ve been such different books, but I can see it working. You can visualize him doing something like Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz as a cross between Little Nemo in Slumberland and Raggedy Ann and Andy, with all of the violence in it made absurd and romantic.

Yeah, I suppose so, although I personally think Johnny Gruelle – who wrote and drew the Raggedy Ann and Andy stories – has a style very similar to Neill’s. I don’t know. I like McDougall’s art for what it is; I wouldn’t want whole books this way. I know, though, that we have different perspectives on what makes appealing children’s book art. Plus, it’s simply very hard for me to wrench myself away from Neill – my Oz is Neill’s Oz, with very little exception.

Well, I thought that McDougall’s art was nice, although Dorothy’s completely bizarre.

She’s been drawn to resemble a child version of Anna Laughlin, the actress who played her in the 1902 musical. (W.W. Denslow tried his own take on the same thing with his Scarecrow and Tin-Man comic strip, “Dorothy’s Christmas Tree,” which went to press at roughly the exact same time. Competitive fellows, weren’t they?) Again, that would have been the popular conception of Dorothy at the time, so it makes sense – rather like how any depiction of Dorothy today looks more or less like Judy Garland, even without specific likeness rights.

The Woggle-Bug looks like an actual insect, as well . . . yeah, they’re more animated and less statuesque than Neill. They’re great. I really liked the version illustrated by Dick Martin, too. That was really warm and rich and nicely rewritten by Jean Kellogg.

Yeah, rewritten to where they’re actual stories! I loved it when I was a kid. I used to take it out from my library and just obsessively go through the pages over and over again. As you say, Martin’s art is lovely – a slightly more “cute,” 1950s take on Neill’s designs – with an appealing, limited color palette. The success of 1960’s The Visitors from Oz led directly to storybook adaptations of the first four Baum novels by Kellogg and Martin the following year. They even publicized the 1960 Visitors with a little cardboard Gump which you could punch out and build! Wouldn’t that be wonderful to have?

Wow! Yeah, it’s good to have the Gump back in it. He needed his own book.

Has anyone ever done that? Get on it, Nick!

I’m going to start right now.

I also used to listen to the cassette version of the Ray Bolger LP (which you can listen to here!). He narrated a handful of the original Baum stories, including – unsurprisingly – the one about magnetism and the one about the magic car.

Oh, I’d forgotten that existed!

I think you’re right that the Queer Visitors from the Marvelous Land of Oz stories are actually more charming than Little Wizard Stories of Oz, which surprised me because presumably, Baum had more actual time to compose and refine the latter. He probably just didn’t care as much by that point.

It’s possible. It’s difficult to write those short little things as well, isn’t it?

He’s not a terrible short story writer. His American Fairy Tales are not bad – quaint and moralistic, yes, but not bad. There’s just not a lot of life in the Little Wizard Stories, at least not for my money.

No, although they’re certainly an insight into the wider Oz franchise, and a reminder that it’s really not focused on the books. The books become the major form, but there are plays, and newspaper comics, and everything. The novels are almost spin-offs, in a way. There isn’t a strict canonicity to these stories at all; Baum’s ideas are proliferating all over the place, and each time they pop up in little promotional ways, they’re slightly different again, to suit whatever it is that Baum’s trying to flog off the back of his van.

It’s around this time that Baum completely gives over to Oz as his way to make money, so over the next couple of books, for instance, we’ll be talking about his forays into the silent film industry. What’s interesting is that following that last great push into other media, by the end of Baum’s life, it had just become the books and very little else. Partly that’s due to their age, and partly that’s due to Baum’s health. In hindsight, it’s easy to only remember the books, when for the majority of Baum’s life, they were a Harry Potter-level phenomenon that took a lot of different avenues within the popular entertainment landscape.

I’m definitely looking forward to Patchwork Girl more than I was, with all the mess and event of a novel, characters having conversations and bickering rather than getting on all the time. That’s one of the problems of these stories: they just kind of…oh, I don’t know anymore. Cut this from the blog!

I think you’ve segued quite nicely into the ending, actually.

I think you’ve segued quite nicely into the ending, actually.

Well, I was trying to. I was certainly trying to.

Is that it?

Yes. Can we go home now?

What do you think? Would you have followed the flight of the Gump in the Philadelphia North American? Do you have fond memories of Crinklink, the terrible squirrel king, and the mischevious imps? Do you ever wonder whether your buttons can hear you? Tell us in the comments section below!

Next Time

THE PATCHWORK GIRL OF OZ

THE PATCHWORK GIRL OF OZ

Read along with us and send in your thoughts! Tell us what topics we should discuss! Be a part of BURZEE!