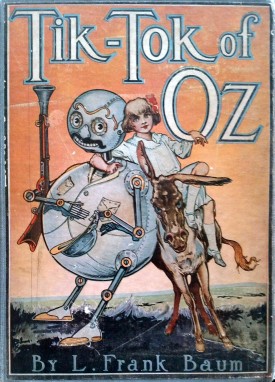

Okay, we admit it: our lives got in the way. Sarah got a brand new, better, more responsible job, and Nick got more responsibilities at his job, and somewhere along the way they both became integral to the 2018 plans of the International Wizard of Oz Club (watch this space). But where did that leave poor little Burzee? On the backburner, of course! Unintentionally though it may be, that couldn’t more resemble the relationship of L. Frank Baum to his Oz books at this point. Despite a new contract that saw him regularly delivering a new Oz adventure, Baum was busy trying to be a celebrity – not an author. Tik-Tok of Oz (1914) finds its roots in The Tik-Tok Man of Oz (1913), Baum’s second and final failed attempt to replicate the success of The Wizard of Oz as a stage extravaganza. Meanwhile, his folly of a Hollywood movie studio was collapsing around his ears. To a child in 1914, though, there were unusual signs of stability: the Oz books had finally become a yearly event!

Okay, we admit it: our lives got in the way. Sarah got a brand new, better, more responsible job, and Nick got more responsibilities at his job, and somewhere along the way they both became integral to the 2018 plans of the International Wizard of Oz Club (watch this space). But where did that leave poor little Burzee? On the backburner, of course! Unintentionally though it may be, that couldn’t more resemble the relationship of L. Frank Baum to his Oz books at this point. Despite a new contract that saw him regularly delivering a new Oz adventure, Baum was busy trying to be a celebrity – not an author. Tik-Tok of Oz (1914) finds its roots in The Tik-Tok Man of Oz (1913), Baum’s second and final failed attempt to replicate the success of The Wizard of Oz as a stage extravaganza. Meanwhile, his folly of a Hollywood movie studio was collapsing around his ears. To a child in 1914, though, there were unusual signs of stability: the Oz books had finally become a yearly event!

Have you read Tik-Tok of Oz? If not, start here . . . .

Well, this was a funny experience, says Nick.

How so? asks Sarah.

Well, first I have to thank you for a copy of the play-script for Ozma of Oz, the first (and only extant) draft of the stage extravaganza upon which Tik-Tok of Oz was based. I dipped into it before reading the novel but didn’t want to spoil the plot for myself. Then when I finished the book, I went back to the play for a comparison. I really don’t know how I’d regard the book if I didn’t know about its previous life. It colored my reading experience quite a bit.

I read most of the play before the book because I knew I couldn’t really be spoiled. I couldn’t remember everything about the book, but I knew there were certain things – like a dragon and a tunnel going into the earth – that were going to be impossible on stage. I’m glad we were both able to read it, though.

I must admit to skimming a bit. Mostly the songs.

Yes, well, it’s a musical comedy – and I guess it’s in the vein of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, or a Wildean comedy of errors. The difference being that it’s not William Shakespeare or Oscar Wilde; it’s by L. Frank Baum, so not nearly as writerly…

Yes, but it’s been interesting to see how Baum structures his narratives. One of their pleasures is a genuinely surrealist narrative logic; sometimes it’s a dream logic, inspired by Alice in Wonderland, I suppose – but in this narrative, the logic that structures everything is, basically, jokes and puns and special effects. That’s actually quite dull to read in the script – but when it becomes a book, it’s so unusual that I found it hard to resist!

I think I’ll go with you on that. I know you like those author’s letters that open each book, and there’s a claim from Baum in this one that I’ve never quite believed:

There is a play called “The Tik-Tok Man of Oz,” but it is not like this story of “Tik-Tok of Oz,” although some of the adventures recorded in this book, as well as those in several other Oz books, are included in the play. Those who have seen the play and those who have read the other Oz books will find in this story a lot of strange characters and adventures that they have never heard of before.

For years, because I’d heard of this Tik-Tok Man of Oz thing, I thought that was Baum trying to have his cake and eat it, too. Now that I’ve read the play, I agree with him. They’re not the same – and I think if you were a child who had seen the play and then read the book, you wouldn’t feel cheated by it. You would get a lot of the things that you saw in the play, but you would also get a bunch of new adventures, too.

That’s absolutely true, but I had a different take on things, at least while I was reading it. I, of course, had no idea about the ways the book deviates from the play. I found myself reading it as if it was a movie novelization. My initial feeling was, “This is so flipping lazy…” Soon, though, I found myself thinking, “This is great! I’m getting the experience of watching this play from a hundred years ago!” It’s not quite that, but it’s quite close, perhaps closer than just reading the script, where dialogue and special effects often just die on the page.

No, I actually agree with that. It’s a very strange thing to get my head around, and I think you’re struggling with it, too. I was also really taken with how much of The Road of Oz was obviously inspired by this play: nobody knows how much of the Ozma of Oz version of the play was rewritten for The Tik-Tok Man of Oz, but since most of the songs are the same in both plays, we can assume they’re fairly similar. Ozma was written in 1909, so I’m left to believe it’s where Baum originates the Love Magnet. And that makes sense – it feels like a very theatrical device.

In a funny sort of way… you have a play with some of the elements of a book, which then gets turned into a book – and then that gets turned into a different book, which then has elements of the play and the book…

But does it make you dislike it? It doesn’t really affect my enjoyment at all.

I think it’s one of the pleasures of the Oz books, the sheer oddness that comes from the different circumstances these books were produced in, and Baum’s choice to hide them in plain sight: like foregrounding the Scarecrow and Tin Woodman in Land of Oz, because of the musical, or having Santa Claus turn up at Ozma’s birthday party. I thought we’d left that behind, sadly, but here we go again with one of the weirdest ones so far – a book that manages to plagiarize about five other books at once. Suddenly, for instance, the Nome King has four different names…

The Play’s the Thing

It’s interesting to me how much Baum wants to reuse ideas, to repurpose them and find a new way of coming at them. It gets to the point – and I thought this was very funny – that in the narration, he lampshades for the reader, again and again, that the army of Oogaboo is structured exactly like the Royal Army in Ozma of Oz, yet they’re not the same.

Yes! There’s also a line of Polychrome’s, about how odd it is that she’s managed to get left on Earth by the rainbow for a second time.

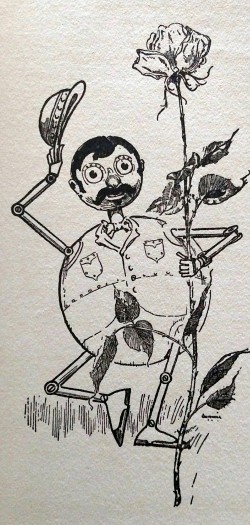

I also wonder if the Rose Kingdom, a very big part of the play that doesn’t last very long in the book, inspired the Mangaboos in Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz. It’s very hard to tell which came first, but I’m willing to bet the play did.

I was wondering, bearing in mind Baum’s “waste not, want not” mentality, whether the Rose Kingdom chapter might not be the Garden of the Meat People – excised from the previous book and modified to suit his publishers’ taste. Unlike the Mangaboos, we have people growing on plants, rather than just people made of plants.

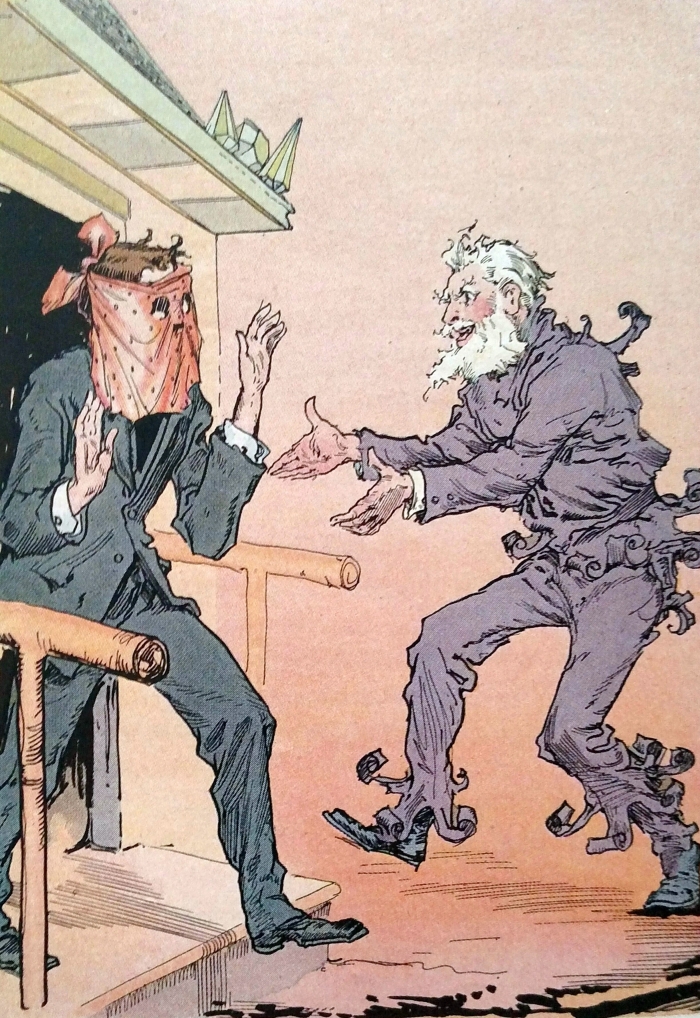

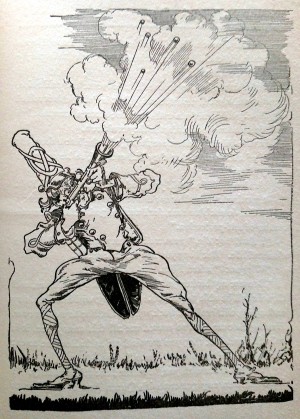

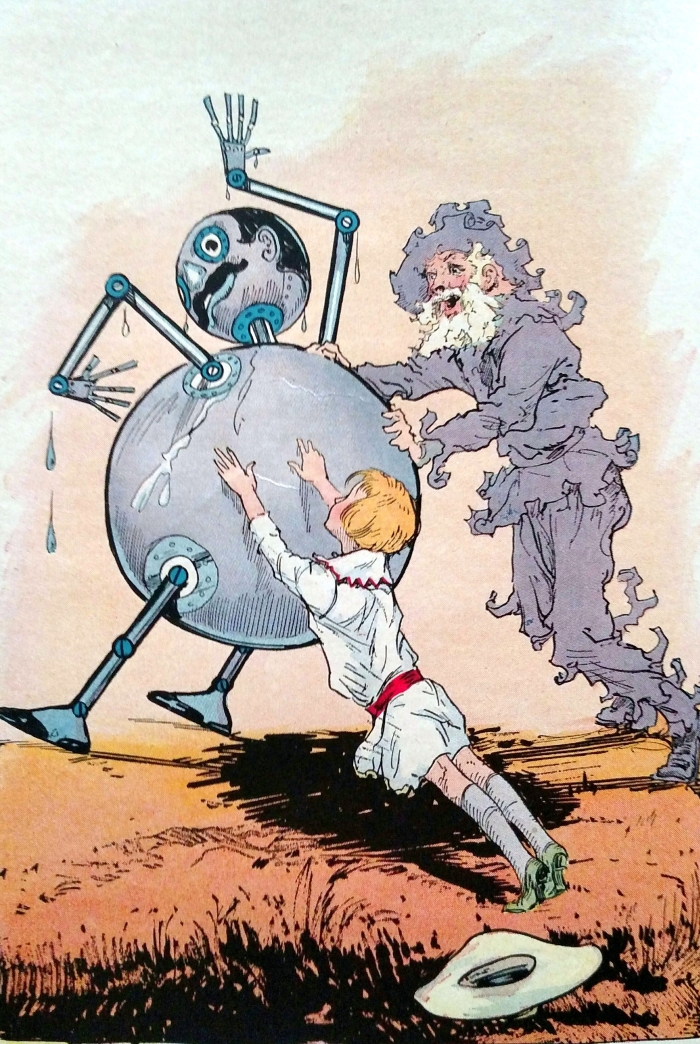

There’s this wonderful illustration of Neill’s that shows the roses coming after them – but in their pots.

Oh, my goodness, yes!

The great part of that is, Baum describes the scene, and I thought: “Surely Neill isn’t really going to depict it like that…” And I turned the page, and – there they were!

The more we talk about it, the more it makes me laugh. And it’s strange because we’ve talked before about how much Neill loves his art nouveau, and this is very like Alice Through the Looking-Glass. Perhaps it’s another instance of Neill modifying the action to make it comic rather than scary, what with the gardener threatening to rip them into pieces.

It’s funny you mention that because Neill has drawn Baum’s description of the roses fairly literally – yet he’s drawn a very different gardener. I agree that the inspiration for the roses must come from Alice’s Garden of Live Flowers, but there’s something rather sinister about these roses with women’s faces, stomping after you in their flower pots. The whole book is an interesting see-saw of beauty and comic grotesquery.

I thought exactly that – that’s the weird thing about these books, the romance and the beauty and the ridiculous jokes, all at exactly the same time.

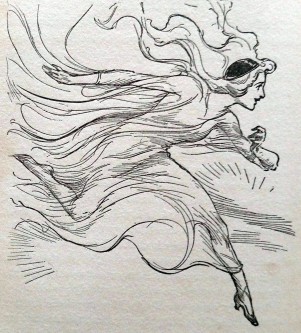

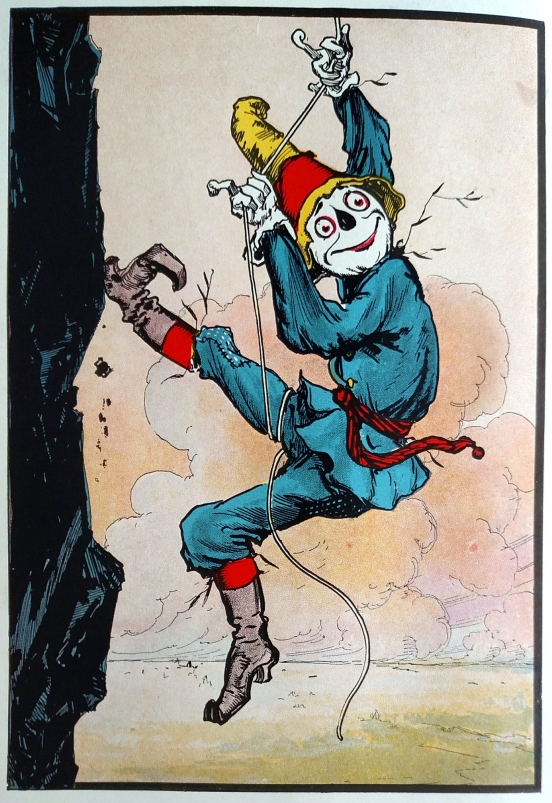

It’s the theatrical roots that account for it, I suppose. There are sequences that aren’t in the play at all, like the encounter with the Queen of Light and her many acolytes. That’s not in the play at all, but it happens in the book, amidst the comedy and adventure, in this beautiful, still little oasis of a chapter. And, of course, Neill takes the opportunity to do a color plate of beautiful women.

That is an incredibly beautiful image, in terms of composition and color. It’s something we’ve seen in previous books, Baum’s strong sense of what you can and have to do on-stage, and then what you can do in a book: whether it’s something ridiculously excessive like Quox, or quieter, more introspective or mystical moments that you just couldn’t serve to a theatre audience. The Queens of Light simply do not inhabit the world where Polychrome falls in love with the Nome King and sings a creepy duet. You feel him testing the freedom of the book, to write whatever he likes.

Peak Baum

I agree with you, and I think what we’re seeing right now, whether he liked it or not, is pretty much peak Baum. I guess I’d had the impression that ‘Phase 1’ of the Oz books – Wizard through Emerald City – is the preferred set of books for most fans. That was never my experience a as child, though. I always found the ‘Phase 2’ books – Patchwork Girl through Glinda – more inventive and more strange and more bizarre, but you have to get used to the idea that Baum’s going to repeat himself occasionally.

Absolutely. That has to be part of the pleasure of it.

And you have to get used to the fact that at this point Baum expects you to be familiar with his world. He reintroduces characters in a way that should be okay for anyone joining the series at this point, but he does it in shorthand. The Nome King in this book is a very broadly defined character, as are Tik-Tok and Polychrome, and I do feel like their original appearances were a little subtler than they are now.

Yes, but I think this is like the party guests at Ozma’s birthday: he’s advertising his back catalogue. He may link up with earlier stories, I never feel like he’s really building upon them. Oh, with one exception, which was a surprise: at the end, when Dorothy wants Betsy to join them, because they don’t have any other children her own age. Ozma is suddenly the older, more responsible, almost adult character, and she gets upset. She goes all wistful, and says, “Am I not your friend and playmate?”, and makes Dorothy blush. It feels like, of all the bits that Baum feels an obligation to return to, to ensure the continuity of Oz, that friendship is of enough significance to him that he has to address it and give it nuance. That said, I found it quite funny how snobby Ozma suddenly seems about letting new people join the series.

I like that she sits somewhere and makes lots of little decisions about who comes into Oz.

“The Land of Oz is not a refuge for all mortals in distress…”

“…But if we want someone in particular, we will take their brother to make sure they stay.”

Yes, the nameless brother.

In the book, known only as ‘brother’.

And in the play, just ‘ugly man’ or ‘ugly’. “So, you’re in a big Broadway production, Joe?” “Yeah.” “Oh, who do you play?” “I play ‘Ugly Man’.”

I Never Promised You a Rose Garden

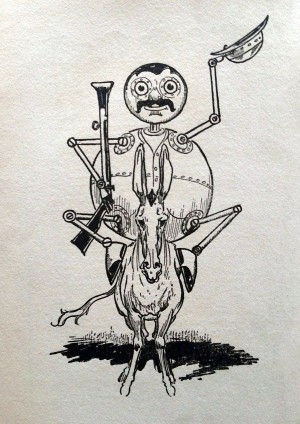

Having, I think, generally praised Tik-Tok of Oz, I have one true criticism: Baum is telling too many different stories in this book. Part of that is, again, because of the play. It’s as if he’s decided that because he’s going to adapt the play, he’s got to include every single character from it. That means that several of them are introduced and then discarded or ignored for very large portions of the book. Something similar happened in Ozma of Oz: the only characters we’re likely to remember from that book’s climax are Dorothy, Ozma, the Nome King, Billina, and the Scarecrow, even though Tik-Tok and the Sawhorse and the Army are there, too, each getting the occasional line. This book opens with some really good chapters in Oogaboo, which I enjoyed – but when I set down the book, I realised that Baum had never actually told me the story of Queen Ann Soforth and her private army. They start off really strong and then fade away. The same thing happens with Ozga – there’s no reason for her to be in the book.

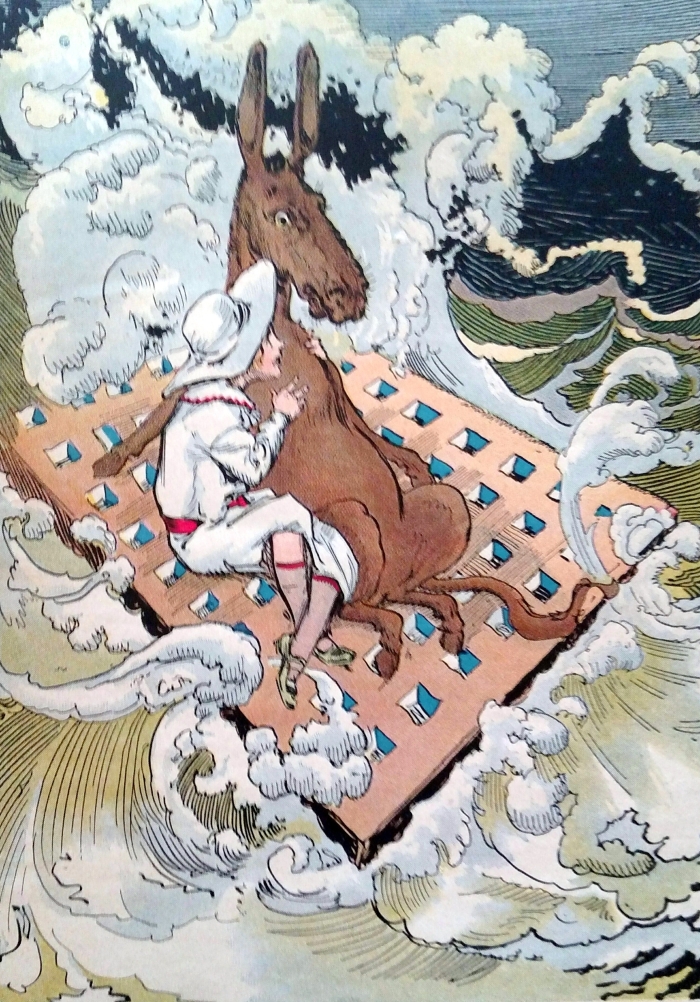

I love the complete lack of imagination involved in just changing all the “M” to a “G” in her name! The extreme version of your point is Hank the Mule, who endures every last crazy event in the novel, including riding on the back of dragon through the center of the earth, without ever saying or doing anything.

At least Neill gets to use him for some comedy.

He does kick a couple of people, but it’s never in any way that affects the plot. I don’t think Betsy is even said to ride on him very much. He’s just there, following everyone around mutely.

Even Tik-Tok – in a way that isn’t surprising, because this is L. Frank Baum naming a book –doesn’t really have that much to do. I felt like, when it was all said and done, I enjoyed the book very much, but it could have been a more satisfying experience if Baum had just worked at it a little harder.

It did feel like a lot of compromises had been made, perhaps to get it over and done with faster. Having a very, very Dorothy-like character just seems like a wasted opportunity.

Yes, Betsy Bobbin’s major characteristic is to say that she’s “never going to be told what to do by any man.” That’s a holdover from the play, but it doesn’t really inform her actions in any way.

The way she’s introduced is so perfunctory. There’s a storm at sea, there’s a girl, there’s a mule, there you are.

And the ship explodes, don’t forget.

It’s so bad it’s good! Towards the end, she falls to the ground, weeping, saying “I’ll never have any home,” and after she’s had her big emotional thirty seconds, the Shaggy Man invites her along for a life on the road. Then she snaps back to normal: “Yeah, all right. It’s raining now…”

The army of Oogaboo just disappears two fifths of the way through. When they show up again in tatters, it’s a good moment, but Queen Anne never goes through any kind of character arc. She’s not even General Jinjur, the character on whom she’s obviously based. Private Files has a wife at the end of the novel – an ex-communicated Rose Princess – but otherwise he’s not done much of anything either.

The Metal Monarch

One thing I would say is, of all people, the Nome King actually gets an interesting story. Baum doesn’t present him as the quintessence of evil in the first place; instead, he’s almost redeemed and likeable by the end. It’s a rare instance of progression in the overall narrative of Oz. Does Baum have emotional investment in the Nome King?

We’ve had three appearances of the Nome King: in the first one he’s an angry child, in the second he’s an out-and-out villain, and in this one he’s a little more…human. As a child, I remember being surprised that he didn’t somehow win out and return from exile. It’s a nice image of him wandering away with is pockets weighed down with gems.

He does come back, right back at the very end, but he’s not the king anymore.

No, instead we’ve got Kaliko, who didn’t even have a name the first time he appeared. He’s steadily progressed to a sympathetic character – unfortunately, something that Baum will completely undo in Rinkitink in Oz. We have a lot of appearances of the Nomes to go, usually centered around either Ruggedo or Kaliko, and they always have to be…adversarial, anyway.

It brings me back to my recurring theme about the oft-described socialist utopia of Oz, and the ways that Baum imagines that perfect state must be undermined in order for us to have an adventure. We have two jealous minor royals here. It’s interesting to see Anne as a queen who doesn’t have the power or the privilege she thinks she deserves.

I like the way the Nome King is used in the new Warner Brothers cartoon, Dorothy and The Wizard of Oz. He’s always “the nefarious Nome King!” – say it in a big foppish squeak – who is almost immediately stopped every time he appears. He thinks he’s the ultimate villain of the piece, but he’s very, very easy to defeat.

That’s very faithful to the books, particularly here where Ruggedo and Kaliko know the army are on their way, and they say, “Bring out the rubber rocks!” The rubber rocks don’t work, so it’s “Send them down a tube to the other side of the planet!” Five pages later: “Oh no, they’re coming back!” Ruggedo’s a little man who talks big but can’t actually get anything done; we’re almost back to the Wizard in the first book, the little man with a lot of theatrics, which feels like a real thing for Baum.

A mutual friend of ours, the writer Lawrence Burton, recently read and reviewed Tik-Tok of Oz without knowing the Oz series at all. He seems to have enjoyed the book, aside from calling it completely inconsequential. One interesting thing, though, is that he reads the Nomes as anti-Semitic figures. I just can’t see it, myself; they come from a long line of magical folkloric beings who guard treasures from the earth – the same mythological origin as Tolkien’s dwarves. I thought I’d throw it at you, though.

Abstractly, the Nomes might fit with that derogatory stereotype, but not enough to make the case for me. We’ve seen explicit ethnic slurs in Baum’s books, and my feeling is that when he does that, he’s expecting a big laugh. It’s not as subtle as the code Lawrence is talking about, because Baum doesn’t really “do” subtle. For a second I thought you were going to talk about one real-world concept that does figure in the book. It’s 1914, and there’s a fleeting reference to conflict in the real world. Do you think there are any other ways that the war of the real world intrudes on this book?

No – and since America didn’t enter the war until three years afterward, that’s not too surprising.

We have the Oogaboos going off on an imperial campaign, but overall, the book is entirely dismissive of war and invasion. Perhaps that’s a fault or an underdeveloped theme – or perhaps he kept it jokey because war was on the horizon. In the play, there is a lot of discussion about Tik-Tok becoming the army’s private soldier because he loves Queen Anne, who only has eyes for the Shaggy Man… Yes, I suppose we should be grateful none of that ended up in the book.

One other thing I’m pleased that Baum didn’t bring across: he dabbles with it in the book, but he never actually makes Ruggedo and Polychrome into a couple.

Indeed. He even downplays the romance between Files and Ozga – they are just ‘close friends’ in the book, and it’s there for an older reader to infer.

Thinks, Speaks, Acts…

Was this the first time you’d read Tik-Tok of Oz, Nick?

Actually, I was certain I had read it – I didn’t remember any of the plot, but I have always remembered the opening scenes, and that weird early line from the Shaggy Man: “Nobody knows what’s going to happen, except the person writing this story.” I remember reading that and thinking “What?!”

Breaking the fourth wall with Uncle Frank! Well, I definitely read it as a child, but I didn’t remember a great deal about it this time. All the visits to the Nome King in different books sort of run together in my head. I do remember the initial exchange between the Shaggy Man and Polychrome, with that pun “I’ll be your beau,” which I had to get my parents to explain. I don’t recall it being a book I really loved, but it also wasn’t one I didn’t like; it was just somewhere in-between, and I have to say that broadly checks out having now read it. I liked reading it very much, but it doesn’t feel terribly consequential and I don’t quite know why.

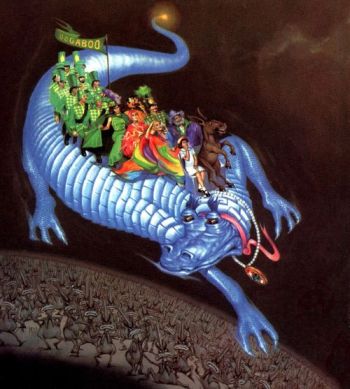

Well, nobody’s ever really in any kind of danger, particularly: they go through the earth to another world where gods and fairies dwell, and they are immediately pardoned and sent back to the Nome King, riding a vengeful beast. It’s a deus ex machina ending, only coming ex machina halfway through the book, so you know it’s all going to be okay. It’s so safe, but at the same time it’s wonderfully ludicrous. A giant, blue, rather polite dragon with an electric lightbulb on its tail – that’s not a big climax, just another scene along the way.

I actually remember, as a child, reading the Del Rey edition with a very nice Michael Herring painting of Quox on the front.

Well, mine was one of those Return to Oz tie-in editions, which only very loosely fit the plot by featuring Dorothy and Billina on the front – alongside Tik-Tok, of course.

You’ve reminded me of something. There are a lot of catchphrases for Tik-Tok in the play, and I’m actually surprised that “Don’t blame me, blame the z-z-z-z-z-z-patentee!” doesn’t get into the book. It’s repeated about twelve times in the play! What does get into the book is “Pick-me-up-pick-me-up-pick-me-up… thank you!” As I was reading that, I was thinking: where have I heard that before? It sounds so familiar… It took me a few days to realize: it’s in Return to Oz.

Ah, of course!

Some little artifact made it from the play to the book to the film, over the course of nearly seventy-five years! It’s probably one of the reasons why there is a credit on the film for Tik-Tok of Oz, not just Land and Ozma. I assume that’s characterization for Tik-Tok, as well as Dorothy falling through the mountain, perhaps inspired by the tube.

That’s mind-boggling! I would add that the plot point about the Nome King saying “All the metals of the world belong to me!” probably comes from the play as well. I don’t think we’ve encountered that concept in Baum before – and didn’t you say that the story of Tik-Tok’s ghost in Little Wizard Stories derives from the play?

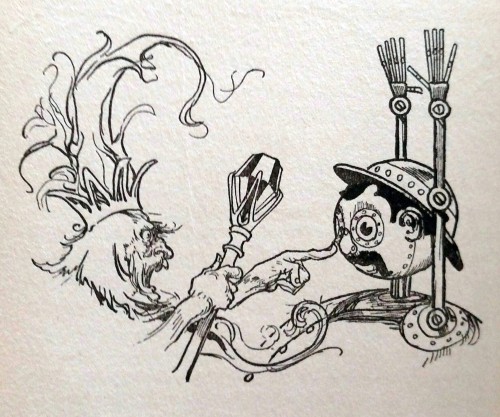

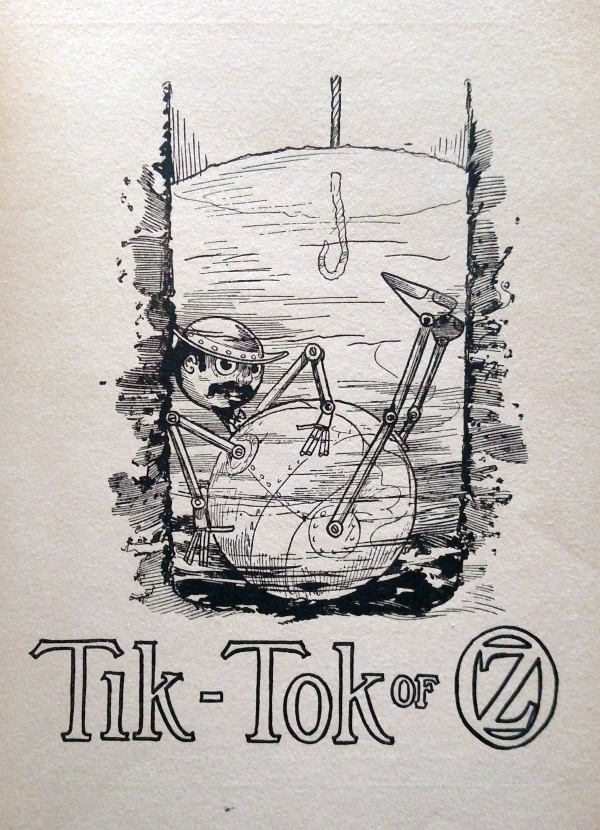

Yes, except that in the play, it’s the Shaggy Man who blows up Tik-Tok, and the Metal Monarch who puts him back together. That’s also the first time we see steely blue Tik-Tok, who will recur across several books, even though he’s referred to as copper several times in this text.

I don’t know whether he’s supposed to be oxidized or something. They do find him after he’s been down a well for quite a while.

I don’t know whether he’s supposed to be oxidized or something. They do find him after he’s been down a well for quite a while.

Then he should really be green!

Well, I’ll just get some yellow felt-tips to colour in all my colour plates and adjust it.

There is one more tiny thing I want to bring up. I’m always fascinated by Baum’s depictions of total authority, whom he seems to like to introduce on the periphery. How did you feel about the Private Citizen, Tititi-hoochoo? It just seemed so out of nowhere, Nick.

That, to me, was just Baum applying a little Carrollian logic and wordplay to make something ordinary a bit more interesting. One thing you can say for Uncle Frank: he will not let even the smallest scene go by in a conventional way. What did interest me was how Tititi-hoochoo only speaks to Tik-Tok, because he’s the lowest-ranked member of the group. It’s a rare moment that Tik-Tok – the first robot in literature, remember – is read as a slave or subhuman figure. It’s the same as when we discussed Scraps, and we concluded that Baum had created not a caricature, but an entirely unique individual – a complete, walking, talking embodiment of oddness and otherness.

…and Does Everything But Live

Did you enjoy the book, Nick?

I did, Sarah – when I realized it was based so heavily on the play, I gritted my teeth and thought I wasn’t going to like it – but the weirder it got and the places it went to and its sheer momentum meant that I enjoyed it much more than I expected.

I also enjoyed it very much, although I know I won’t remember a bit of it next week! It’s amazingly easy to read, it ticks along at a great pace, but there’s not a lot to grab on to that we haven’t seen before. Enjoyable it is, I just don’t think it sticks in the memory the way of some of the other books.

With some Oz books, I think you might get more out of it if you were like our friend Lawrence, coming to these ideas for the first time and not knowing they belong elsewhere. As a fan, though, you can actually have your cake and eat it, too, because you can spot those reused ideas and just revel in the absurdity.

True – and you’ve actually dovetailed into my final point. Every time, we ask ourselves if we would give this book to a child. This time I’m saying, yes, I would – particularly to a child who hadn’t read an Oz book before, because I feel they might get a lot out of it! It’s fun, it’s very exciting, there’s a lot of interesting things going on, and I feel like if you hadn’t encountered those ideas before you would enjoy them even more.

Agreed. And I would also like to officially patent the idea of a direct novelization of that original, 1902 Wonderful Wizard of Oz musical. I think it would be tremendously interesting and fun – and odd, of course!

Ha! “Don’t blame me, blame the zzzzzzzz patentee!”

What do you think? Does Tik-Tok tick along to a peak performance? Or is it merely a broken clock that tells the right time twice a day? Tell us in the comments section below!

Next Time

THE SCARECROW OF OZ

THE SCARECROW OF OZ

Read along with us and send in your thoughts! Tell us what topics we should discuss! Be a part of BURZEE!

Illustrations are photographed from the book collection of Sarah K. Crotzer, are used without financial gain as examples of the original publications, and remain the property of their original creators and publishers. Please don’t steal them; go buy the books instead.

I didn’t see the nomes as specifically antisemitic so much as relating to and possibly derived from folk tales with some antisemitic element or root, those hunched ‘races of little subterranean men hoarding their gold and precious metals’ which, as I wrote, ‘I suspect this was simply Baum borrowing from the folk myth of the Wandering Jew rather than anything approaching any kind of racial allusion, given that the same would contradict the generous spirit of the book as a whole.’ Also, I’m not sure I meant to imply that the book was inconsequential exactly, just that it’s a different kettle of fish to Crime & Punishment (and for the record of the two I prefer Tik-Tok). Nice to get mention though!

LikeLike

Ok, first, I choked on my lunch at “I’ll just take some yellow felt-tips…”

I felt largely the same way you two did. I definitely had the Del-Rey edition and the image of Quox is always in the forefront when the book is mentioned. (Also nice reference in “Wicked” to it)

I think overall, it’s a good, solid book when he’s not reusing the theatrical elements from the stage play, which was part of my problem with Land of Oz, too.

I will say, I disagree with your assessment of Kaliko in “Rinkitink,” but that will be better tackled later.

LikeLike

One of the things I’ve mentioned in the past that I’ve always found interesting in Tik-Tok, is the overal theme of displacement – everyone in it seems to be lost or exiled. Betsy is lost at sea, the army of Oogaboo is lost in the mountains, Polychrome has lost her rainbow, Tik-Tok is lost in a well, the Shaggy Man’s brother is lost in the Nome kingdom… The Rose Princess is exiled from her kingdom and the Nome King ends up exiled from his. Even Quox is sent from his home as a punishment. That’s a lot of wandering characters looking for a story!

LikeLiked by 3 people

The script of Ozma of Oz is not the only extant script of The Tik-Tok Man of Oz, though it is the most complete. The script for the first act of The Tik-Tok Man of Oz exists, seemingly as it appeared onstage, at least early in the show’s run. This is the script that the revival at Winkie Con 50 was based on, supplemented with the Ozma of Oz script. I discuss all known versions of the script in my article on the play in the Winkie Con 50 program book and reproduce sample pages from both the Ozma of Oz script and The Tik-Tok Man of Oz script. I’ve seen other discussions ignore The Tik-Tok Man of Oz script and can’t understand why.

LikeLike

Oh, that’s fascinating! Thanks. So now, all I have to do is find a copy of that program…

LikeLike

The timing is terrible. Hungry Tiger Press had copies of OzCon (formerly Winkies) program books from the past ten years. David and I took them to OzCon 2018 last weekend and put them on the OzCon sale table and they all went fast. So I’m not sure now where to get one easily. But there are maybe 400 of the Winkie Con 50 program book in print. Surely it can’t be too difficult.

LikeLike

Well, it’s my own fault for not realizing there was an unapproved comment all this time. I’m sure I’ll catch up with a copy one day. 🙂

LikeLike