A lot has happened since our last installment. Sarah became the editor of The Baum Bugle, which makes her very happy. Nick became editor of its sister publication, The Oz Gazette, which makes him very happy, too. Nick is also thrilled to have finished his doctorate, and Sarah – well, she’s still figuring out how to effectively teach 110 students per semester, frankly. One way or another, the first half of the year just slipped by for both of them; now, here they are, back and ready to go. It’s sad to realize that even as their lives improve, Baum’s life – at the time of The Scarecrow of Oz (1915) – was starting to wane. His most recent theatrical extravaganza hadn’t been as successful as he’d hoped, and his silent film company was an outright disaster. That left just one successful arena to fall back on: the yearly Oz book, of course. This time, though, it feels like Baum’s heart may not have in it – or, at least, that his head was somewhere else…

A lot has happened since our last installment. Sarah became the editor of The Baum Bugle, which makes her very happy. Nick became editor of its sister publication, The Oz Gazette, which makes him very happy, too. Nick is also thrilled to have finished his doctorate, and Sarah – well, she’s still figuring out how to effectively teach 110 students per semester, frankly. One way or another, the first half of the year just slipped by for both of them; now, here they are, back and ready to go. It’s sad to realize that even as their lives improve, Baum’s life – at the time of The Scarecrow of Oz (1915) – was starting to wane. His most recent theatrical extravaganza hadn’t been as successful as he’d hoped, and his silent film company was an outright disaster. That left just one successful arena to fall back on: the yearly Oz book, of course. This time, though, it feels like Baum’s heart may not have in it – or, at least, that his head was somewhere else…

Have you read The Scarecrow of Oz? If not, read it here . . . .

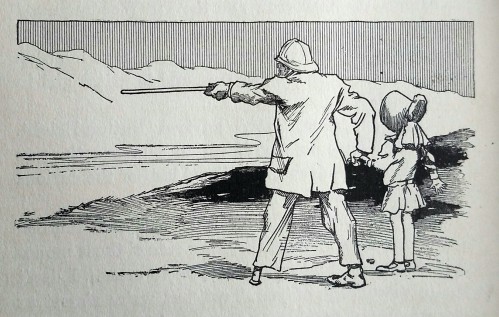

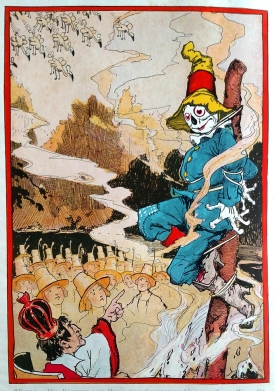

It was interesting reading this again because of how little I was able to recall, says Sarah. This is probably one of the earliest Oz books I read, because our local public library branch – which was about the size of a trailer – had one Oz book in it, and that was a white edition paperback of The Scarecrow of Oz. I had read it backwards and forwards by the time I was seven years old. As it turns out, I only remembered the big moments, chief amongst them the snow outside the Bumpy Man’s house. I remembered Trot and Cap’n Bill in the underground caves, and I remembered Gloria’s heart being frozen. That last is because of the silent picture, His Majesty, The Scarecrow; a frame from the movie appeared in Allen Eyles’ World of Oz book, and I was quite fascinated by it. Finally, I remembered the sequence of the Scarecrow shrinking Blinkie – but that’s because my mom reworked that illustration as a topper for one of my birthday cakes.

It was interesting reading this again because of how little I was able to recall, says Sarah. This is probably one of the earliest Oz books I read, because our local public library branch – which was about the size of a trailer – had one Oz book in it, and that was a white edition paperback of The Scarecrow of Oz. I had read it backwards and forwards by the time I was seven years old. As it turns out, I only remembered the big moments, chief amongst them the snow outside the Bumpy Man’s house. I remembered Trot and Cap’n Bill in the underground caves, and I remembered Gloria’s heart being frozen. That last is because of the silent picture, His Majesty, The Scarecrow; a frame from the movie appeared in Allen Eyles’ World of Oz book, and I was quite fascinated by it. Finally, I remembered the sequence of the Scarecrow shrinking Blinkie – but that’s because my mom reworked that illustration as a topper for one of my birthday cakes.

Well, that sounds like a lot of memories to me, says Nick. I have very little memory of this book at all. I had it in my teens, only because you sent it to me. When I was small, I had another great Oz reference work, The Wizard of Oz: The Official 50th Anniversary Pictorial History. It had a splendid spread of all the book covers, like an Argos catalogue of impossible dreams. I remember looking at The Scarecrow of Oz.

Well, that sounds like a lot of memories to me, says Nick. I have very little memory of this book at all. I had it in my teens, only because you sent it to me. When I was small, I had another great Oz reference work, The Wizard of Oz: The Official 50th Anniversary Pictorial History. It had a splendid spread of all the book covers, like an Argos catalogue of impossible dreams. I remember looking at The Scarecrow of Oz.

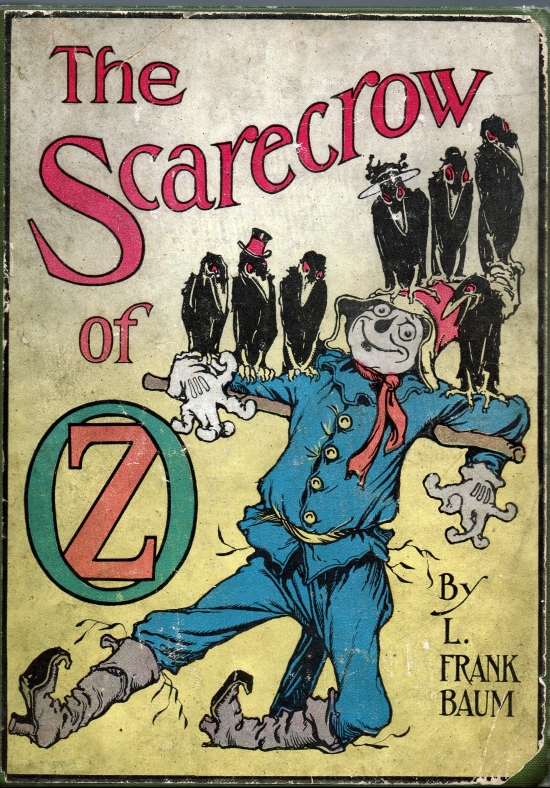

That’s one of my favourite Neill covers. It’s lots of fun. I like the little crows in hats!

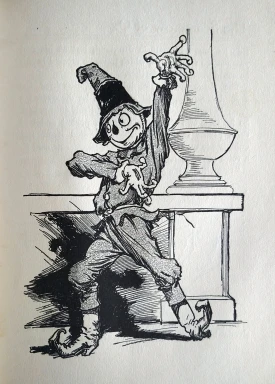

One of the upsides of framing whole books around specific character is this gallery of fabulous character portraits. I always knew this book at least had the Scarecrow in it – although, to some extent, that may have turned out to be misleading.

I don’t know what you’re talking about, Nick. It’s not as if the Scarecrow doesn’t show up till page 169 of his own book…! Oh, wait. That’s exactly what happens.

Anyway – back in my youth I was terribly excited to read something from that spread of titles. I had The World of Oz too, so it was interesting to recognize the plot of His Majesty, the Scarecrow of Oz, which I never expected to see – certainly not with the ease in which we can watch it now! Before re-reading it, though I couldn’t really have told you what happened in The Scarecrow of Oz. It’s just so restrained for an Oz book, probably because it is based on a rather conventional movie.

Although I knew the Scarecrow didn’t show up for about half of the book, something I only realized as I approached it was that I had no recollection of how the story resolved. How most of it fit together was a surprise to me. I think, for what this is – Baum’s unfinished third Trot and Cap’n Bill manuscript, and a novelization of His Majesty, the Scarecrow – it’s actually a fairly tight piece of work. I can’t believe I’m saying that…

Trot’s Adventures Underground

Let’s not get ahead of ourselves. We start the story with Trot and Cap’n Bill, characters that I had no knowledge of when I first read this book. For BURZEE we’ve actually read The Sea Fairies and Sky Island in sequence, the latter of which we really enjoyed. Are you pleased to see these characters here, Sarah?

I’ve come to really like the characters of Trot and Cap’n Bill; I’m happy to see them in Oz. I’m maybe happier to see them than some of the Oz characters we’ve come to know a bit better – especially Trot, who is still very gung-ho and forthright. I am a little confused now, because at one point Baum suggests that Cap’n Bill isn’t “as old as he could be.” I spent a long time trying to work out what age he could actually be. I think what Baum is implying is a man who has lived hard and retired a little early.

I think he works well in the Oz books because he’s a big character, which suits Baum’s style – and he’s also an older gent, still up for an adventure but less heroic a figure than Trot. Like other Oz characters, he subverts a few masculine characteristics of the time.

He’s a mix of the Shaggy Man and the Wizard but, I think, more believable than either of them.

He’s less easy-going, isn’t he? In the same way that Dorothy remains a Kansas farmgirl, Cap’n Bill belongs to our world; he’s more earthly than the Wizard or the Shaggy Man (what with his magical love magnet). One of the fun recurring features of the Oz books is someone very mortal and “meat and potatoes” meeting someone like the Bumpy Man who drinks lemonade like water and shovels popcorn from his door. Cap’n Bill doesn’t want to drink lemonade for breakfast, but he’s still up for an adventure.

When I was reading the book as a six-year-old, I knew that Trot and Cap’n Bill talked about having encountered Button Bright before, but I never really thought about where that missing story was. Baum achieves a very strange “meta” level of self-reference, having characters talk about reading the Oz books and then encountering the characters that they recognize. Trot talks about already knowing who Dorothy and Ozma are long before she meets them, so it’s not a big shock, perhaps, that she knows Button Bright, too. My childhood brain papered right over that crack.

In his introductory letter, Baum says that children have petitioned for Trot and Bill to join the world of Oz. Reading the book as part of a sequence, though, it seems obviously based on an abandoned manuscript, the third in a trilogy abandoned due to poor sales.

Yes, and I think I can see where the third book ends: around the time they get to the Bumpy Man’s cottage. It’s interesting because you called it, Nick. When we were discussing Sky Island, you guessed that the next book would be something like Underground Island, and that’s exactly right! In spite of (possibly) identifying where Baum left off using that manuscript, I don’t think it’s awkwardly done. How did you feel about it?

I found it interesting, because there was just enough left to guess at what sort of book we would have got: the Ork’s name seems to come from an extinct Auk, so I suspect we would have had a few dinosaurs, talking fossils, maybe even prehistoric man. But I was a little disappointed because Sky Island had been so well constructed, with interesting ideas and lots for Trot to do. A lot happens in these first few chapters of Scarecrow, but there’s nothing really to suggest it would have been a proper novel; it’s just another travelogue. I think we really benefit from moving into that plot from the movie.

Romance of the Silver Screen

Did you watch the movie, Nick?

Did you watch the movie, Nick?

Yes – and of course, it’s great to see, and yet it’s rather odd. I’d forgotten how much it follows the plot of The Wizard of Oz. After Tik-Tok of Oz, it’s beginning to feel like Baum will continually return to things he’s already done and smash them up with something else, like Dracula meets Frankenstein meets Abbot and Costello. Most of the time, you just have to get on board with it.

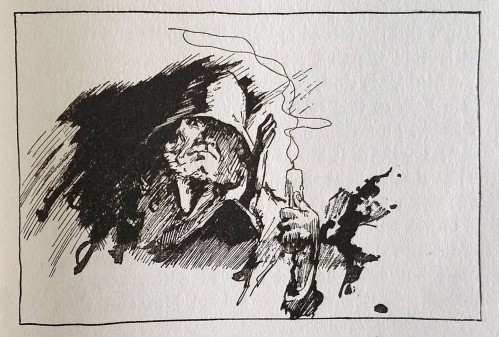

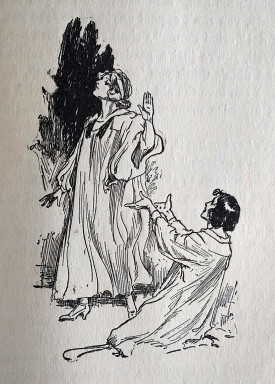

I was struck by the shapelessness of the movie. Lots of it is set around special effects sequences, like freezing Gloria’s heart or the – ahem – magic wall of water. It doesn’t really have a beginning or an ending (or at least, an ending that offers much resolution), so it’s interesting to me that Baum chose to adapt it into this book. In particular, what he actually took from it was the romance storyline, something that he otherwise seemed to feel did not belong in Oz. He even gave interviews to that effect. I think it makes for some memorable material, though; the scene with the witches gathering to freeze Gloria’s heart is a corker, both on-screen and on the page.

I was struck by the shapelessness of the movie. Lots of it is set around special effects sequences, like freezing Gloria’s heart or the – ahem – magic wall of water. It doesn’t really have a beginning or an ending (or at least, an ending that offers much resolution), so it’s interesting to me that Baum chose to adapt it into this book. In particular, what he actually took from it was the romance storyline, something that he otherwise seemed to feel did not belong in Oz. He even gave interviews to that effect. I think it makes for some memorable material, though; the scene with the witches gathering to freeze Gloria’s heart is a corker, both on-screen and on the page.

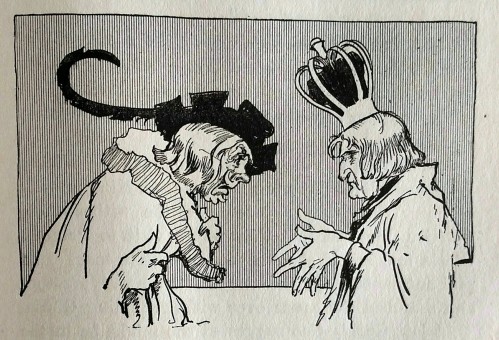

What works is that, in a sense, he is returning to his first Oz book and integrating the fairy tale story with a dramatic narrative. Blinkie might be the Wicked Witch of the West returning in a new incarnation, but in complete contrast to that first book, she and King Krewl are proper villains who have goals, do things, and have to be confronted. Blinkie is very good fun, for the little that she does.

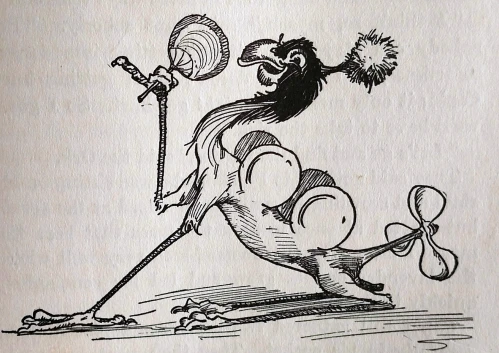

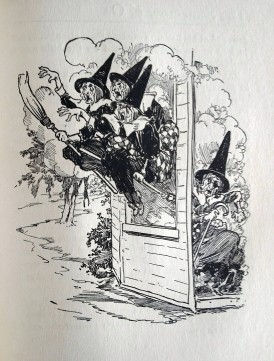

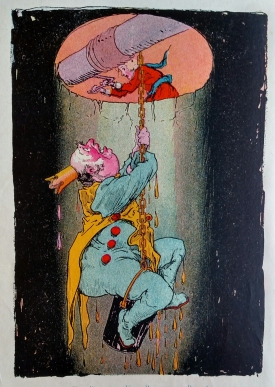

She is – and while I’ve always thought, “Why bring the Scarecrow in to heroically save the day when he’s so easy to defeat?” I still find it quite entertaining. I’m curious about her costume, though. In the film, her costume design seems to have been directly inspired by Denslow’s Wicked Witch of the West; then, in turn, Neill seems to have been inspired by the film…

Yes, it’s like how in Tik-Tok of Oz we identified a line of dialogue in Return to Oz that was taken from the 1913 stageplay. That recycling process inadvertently injects a little Denslow into a Neill book!

It’s an especially odd effect because, unlike Tik-Tok – where you could clearly see the origins of the book as an adaptation of The Tik-Tok Man of Oz – the more overt Wizard plot elements have been left behind. If we didn’t know that it came from a silent movie rehash of Wizard, I don’t think anyone would guess. Baum is at least successful in disguising his remakes as much a possible.

I agree that it’s a successful plot transplant. The tone of the novel is very different to the movie, and the fact that romantic narratives don’t normally have a place in Oz remains somewhat consistent: Trot, after all, is so disdainful of the whole thing. She’s constantly saying things like, “Oh, you could do a lot better than Pon, love.” The Ozzy strain definitely dominates. You never care about Pon and Gloria, really; the focus is always on the more childlike, irreverent people. There’s really no clue that the story belongs anywhere but in a book, perhaps because it’s such a very “fairy tale” setup.

Indeed, Jinxland feels like a small European country rather than an American city. There’s a monarchy, courtiers, witches, the aristocracy…

There’s money and wealth as a drive toward corruption.

It feels more like an offcut of Mo or Ix than anywhere else we’ve ever visited in Oz; perhaps in primitive times, all of Oz was like this! Then they wised up.

I do feel there’s a cinematic shift in the second section. There’s a lot of spying and watching, unlike in Sky Island; they’re simply not permitted to play an active role because it would mean Baum rewriting his story. Baum even has Gloria wandering up and down, so frozen-hearted that she won’t listen to what other characters say, as if Trot and Button Bright have wandered into a screening of the movie and are shouting at the screen. It’s not helped by a tendency for Baum to write characters who don’t really care what happens to them. Sometimes “laconic and flip” tips over into “totally disengaged from the action.”

His Brainy Majesty

Then, Sarah, we have Glinda watching the action from somewhere else, and as in The Emerald City of Oz, not actually communicating with Ozma about the threat. She just takes unilateral action.

Glinda has really taken on that Charlie’s Angels role of the powerful entity who sends agents out to solve her problems. I think it’s interesting that she mentions Jinxland as being “on the map” – if the kids of 1915 were paying attention, they would have noticed that she meant the map from Tik-Tok of Oz‘s endpapers. Forward planning!

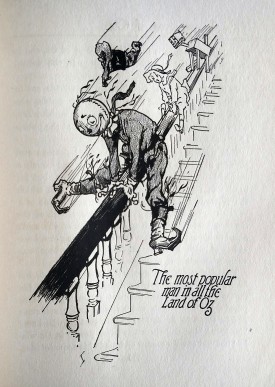

Her action is to deploy – of all people – the Scarecrow. Her main rationale seems to be that he is “the most popular man in Oz.”

That’s hilarious. She might just as well send out Dorothy because she’s plucky or the Glass Cat because she’s proud. Within the reality of the story, there’s absolutely no reason to do what she’s doing. In our world, though, there’s a very practical reason: sales. At this point it’s pretty obvious that the Scarecrow is – with Dorothy – the most popular character in the Oz books. At least one of the two of them is a protagonist in nearly every book, sometimes both. At this point, Baum has essentially abandoned the Tin Woodman and (especially) the Lion, and he’s reinvented the Wizard as a far more avuncular character. Of his original team, only Dorothy and the Scarecrow are still commanding top billing – and while it isn’t a surprise to me that Dorothy is a fan favorite, I’m curious what it is about the Scarecrow that tweaks the audience’s interest so hard. Is he just a strangely appealing figure to children, or was there that much leftover goodwill from the popularity of Fred Stone?

That would make sense. In some sense, didn’t the Scarecrow become an icon of Oz and part of its branding? I don’t know if it’s also Baum’s own taste that, of all the Oz characters, he’s literally the earthiest, most American character. The Tin Woodman represents something slightly othered, the Lion has exotic overtones, but the Scarecrow is a bit of Kansas farmyard brought to life. It’s funny that in the movie, Baum gives the character a backstory: he is animated by the magical spirit of the corn, which is symbolized by ersatz “Native American” dancers. There’s something, perhaps, of the land about him, and he’s a clever but not urbane intellectual.

Absolutely. How do you feel about a book, though, that’s called The Scarecrow of Oz where he features so little? I did the math and he genuinely doesn’t show up for 60% of the story.

Halfway through the book I didn’t mind. I thought, well, here is he is, he’ll turn up and resolve the situation. Unfortunately, that hope is undone when the Scarecrow singularly fails to help anyone and is, instead, nearly burnt at the stake. He has to be saved by a character who is more or less called in from another world at the last minute. That, in fact, is the moment the Scarecrow exemplifies the disengaged quality of Baum’s characters, especially because he’s so invulnerable. He doesn’t even fear being burned to death; he’s just conscious that his friends will be sad.

Have You Had Enough Yet, Mr. Baum?

I think Baum has a very strange take on things like self-destruction or “love that can never be”: if it can be avoided, it should be, but if it can’t – that’s how it goes. It’s odd – he doesn’t seem particularly concerned about these things, and it is strange that it comes into his characters’ point of view. On the other hand, he may be trying to prevent children of a delicate sensibility from being upset. Do we think it shows that Baum cares less? Are we at an Arthur Conan Doyle-type place where Baum is only writing these things because he has no choice?

For me, the whole book smacks of disengagement and disinterest – but I also read elsewhere that Baum described it, more than once, as his favorite of the series. He may have been more satisfied with its conventionality, whereas I see the wildness of earlier titles as their main virtue.

There’s a moment in his authors’ note where he says, “It takes more and more Oz books to satisfy old and new readers, and there have been formed many Oz Reading Societies … When the children have had enough of them, I hope they will let me know and then I will try and write something different.” Well, good luck with that, Frank. They just want Oz.

I love the sound of Oz Reading Societies. Can we join? Is there any evidence that those really existed?

I have no idea! I do like the suggestion, though, that everybody brought their books and read aloud – taking it in turns, or what? At this point there were only nine Oz books, so you wouldn’t have needed to make a particularly large collection.

It makes me think of Christian Scientist Reading Rooms. What an idea that every small town might have its little Oz Reading Room where you go in and get schooled in Oz. Actually, whilst I don’t believe Baum when he says people were petitioning him for more Trot, it can’t have been an illusion that these books were popular, so the idea of Oz fan clubs makes sense to me. I will choose to believe that Baum’s knowledge of them was just slightly distorted.

Well, we know there were fan clubs by the 1920s because Reilly & Lee supported them, so…

There’s also an interesting direct testimony quoted in my copy of the book. William Lindsay Gresham was a novelist and he described how returning to The Scarecrow of Oz, which he was read when he was a child, consoled him after his divorce. Evidently, these books were read successively down a number of years – this is fourteen years since the first book, after all.

It’s a little like the Harry Potter series, which continues to be a phenomenon after twenty years, spawning new stories. JK Rowling is even going to make a novel out of a movie, with Fantastic Beasts…

A movie which was a book is going to become another book? What a tribute to Baum!

…And You, Mr. Neill?

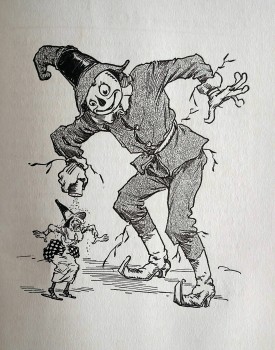

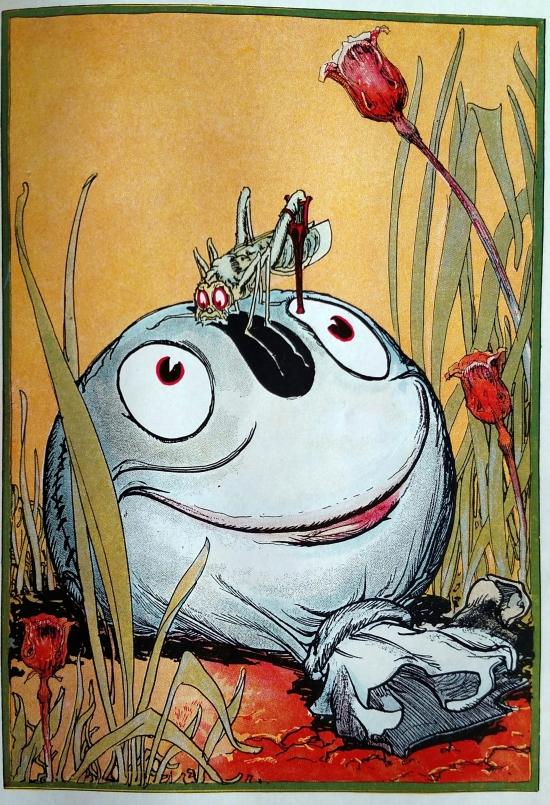

What do you think of Neill’s artwork in this book? His black and white work is particularly strong, I think. There are some very, very nice illustrations. He’s now fully into the period I think of encapsulating his best work – the mid-teens to the mid-’20s, basically. I do find myself wondering what the characters are doing in the endpapers, though. I always assumed they were doing the conga, but that actually wasn’t popularized for another 20 years…

The color plates are literally illustrating, not illuminating, the text – and the coloring actually reminds me of the Little Wizard stories, with all those garish images. Overall, I found them pretty unappealing, apart from the image of Cap’n Bill perched on top of the Scarecrow’s head in the form of a grasshopper. I do remember you telling me, when you sent me the book, how you liked that one.

At this point Neill isn’t choosing, or coloring, his own plates. I think they’re okay, but none of them strike me as being overwhelmingly pretty, unlike, say, Sky Island. (Part of this is simply down to the person in charge of the colors; compare the much more delicate coloring of the plates in Sky Island and how much more attractive those image are as a result.) That plate of the Scarecrow and Cap’n Bill was reproduced on the back of the 1960s/70s white edition; it’s the best composition of any of the plates, and a nice image overall. The others I can take or leave. I definitely prefer the black-and-white work.

For me, that plate depicts one of the best moments in the book: you’ve got your hero who’s been dismembered but still alive and fairly cheerful – and one of your other heroes has been turned into a grasshopper and sits on his head, definitely not cheerful. Unfortunately, about five minutes later, everybody else just happens to walk past and they all get together. After that point, it might have been better to have paired up some of those characters and give them each a bit of the story, with lots of fun conversations and arguments.

With Faint Praise

So… Nick, did you enjoy reading the book?

I don’t think I disliked reading it, and I was surprised at how smoothly it was put together. I actually read it very, very quickly, and the only bits I really didn’t like were the pointless page-filling at the end, with the Scarecrow falling in the river and the magic food – but I can’t say I enjoyed it, unfortunately. How about you?

I did enjoy it. I thought it was very pleasant and easy to read. Having said that, I don’t think it’s ever going to become a favorite of mine. I am predisposed to loving a book called The Scarecrow of Oz and as we’ve seen, it didn’t stick in my memory. At this point, I’ve got to ask: would you give this book to a child?

No – I think less than any of the other ones we have read. It’s all just too static. After we get through the mountains, it’s all set in the one place. There’s not much momentum, not many laughs or scares or strange creatures – so no, I wouldn’t. I think it would be off-putting. What about you, Sarah?

I’m not sure I see it quite so harshly. I think it would be quite easy to give to a child; it’s even got some more stereotypical fairy tale aspects that a child might find appealing. The problem for me is that the book starts to tell one story, which I think is going to be appealing to a certain kind of child reader, and ends halfway through to pick up another story, which is going to be interesting to an entirely different kind of child reader. Unless you’ve got a child who is interested in a wide variety of plots and adventure stories and fantasy narratives, they’re going to be bored with at least one half of the book. Unlike some of the other books we have read in this blog, though, I didn’t find any old-fashioned attitudes that really bothered me; I didn’t find anything to be concerned about or to reframe in the context of 2018. It’s just not Baum’s most developed story.

That’s fair enough. I think we came away with slightly different feelings about this book, but we can definitely agree that it’s not badly written. It is, in fact, something of a feat for Baum to marry together multiple sources. Next time, we’ll be talking again about undeveloped stories, in particular one that didn’t even develop an ending – but soon, I think, we’ll see just how satisfying Baum’s Oz books can be when he’s fully engaged with them and their imaginative possibilities.

Were we too krewl to this book? Do you have many happy childhood memories of The Scarecrow of Oz? Have you always wanted a pet Ork (and are you upset that we barely mentioned him)? Tell us in the comments section below!

Next Time

RINKITINK IN OZ

RINKITINK IN OZ

Read along with us and send in your thoughts! Tell us what topics we should discuss! Be a part of BURZEE!

I have almost no memory of this one– it was definitely not a favorite of mine as a kid. I didn’t read the Trot and Cap’n Bill books until last year (whenever you all did them), so they didn’t mean much to me as people, and like you say, it tells us much less about the Scarecrow than TIN WOODMAN does the Tin Man.

LikeLike

My local library had The Sea Fairies and Sky Island, so I guess I’m in the rare position for modern times of already knowing Trot and Cap’n Bill when I read this one. As for the Cap’n’s age, doesn’t he say he’s sixty in Sky Island?

LikeLike