After our long and expansive discussion of 1900’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, we knew it was going to be hard to move straight on to the next Oz book, which was published a full four years later. Having already exposed ourselves to The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus, we decided to look at the other two full-length fantasies L. Frank Baum published before 1904. One was a book both of us had read a long time ago; one was a book we had never read before. What we discovered was an author who hadn’t quite found himself yet: still experimenting with his craft, trying to determine what made a good fairy story…

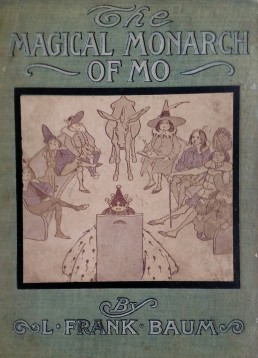

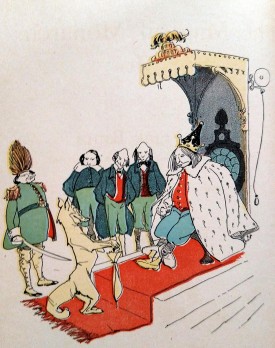

Originally published as A New Wonderland in 1899, The Magical Monarch of Mo was retitled and slightly revised in 1903 following the success of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Either version of the book is a collection of loosely linked fairy tales that focus on the royal family of a topsy-turvy fantasy country where it only rains lemonade, candy grows on trees, and nobody ever dies. Among the “surprises” included are the loss and recovery of the king’s head; the invasion of a cast-iron giant; the peculiar punishment of a fruit-cake island; and the bravery of a prince against the monstrous Gigaboo.

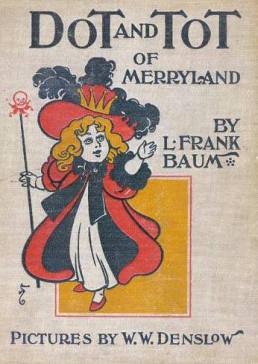

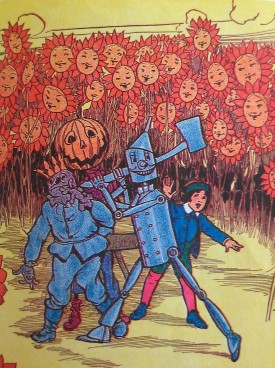

In Dot and Tot of Merryland, the initial followup to the success of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and the final partnership of L. Frank Baum and W. W. Denslow, recuperating rich girl Dot and gardener’s boy Tot take an impromptu journey by boat to Merryland, through seven magical valleys, and into the unknown beyond. Along the way, they encounter mixed-up clowns and talking cats, find out how babies are delivered by stork, discover the last resting place of things that are lost, and are crowned prince and princess of Merryland by its fairy queen.

In Dot and Tot of Merryland, the initial followup to the success of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and the final partnership of L. Frank Baum and W. W. Denslow, recuperating rich girl Dot and gardener’s boy Tot take an impromptu journey by boat to Merryland, through seven magical valleys, and into the unknown beyond. Along the way, they encounter mixed-up clowns and talking cats, find out how babies are delivered by stork, discover the last resting place of things that are lost, and are crowned prince and princess of Merryland by its fairy queen.

Perhaps, says Sarah, we should begin at the beginning. We made a conscious decision to read two of Baum’s non-Oz fantasies together, in part because we thought we wouldn’t have as much to say, or as much personal nostalgia, as we would with an Oz book. Do you think that was a good decision? Were the two books different enough from each other?

Yes, says Nick, for me it was very interesting. These books really shine a light on Baum at the time he was writing The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. I think I’ve got a really clear idea in my head of what Baum was trying to get at around this time. He seems to be experimenting with different approaches to children’s books, from really larky to really lazy and even patronizing.

I think the thing that struck me the most is he’s still sort of working his way out of the fairy tale tradition. The Mo stories – sorry, surprises – are very thinly linked fairy tales, and Dot and Tot is incredibly episodic, even more so than Wizard.

Baum isn’t really constructing novels yet. He’s still telling loose stories of varying tones and styles, which is actually quite fascinating. For my money, the Mo stories (or at least, how they appear in the 1903 revision) are the closest to resembling Baum’s later work. They have a lighter, less moralistic touch, and they exhibit quite a bit of Baum’s trademark punning humor. They’re still transitory – they’re incredibly violent compared to his later stuff – but I at least recognize the Baum “voice” in them, if that makes sense.

I agree, and I think his influences are clearer than ever in those stories. They start off with stuff that feels more like Alice in Wonderland mixed with some ultra-conventional, Land of Cockaigne fantasy stuff, which is inevitably parodied because – as we know – Baum wasn’t a pie-in-the-sky sort of person.

That’s actually a good point; we’re still in a period when Baum’s writing about princes and princesses and dragons, and he’s only just starting to flip those stereotypes on their heads.

I think there’s a really strong feeling of Grimm and Hans Andersen here, too, and he’s really only undercutting them a little bit, usually through tone. The idea of eternal life, which is quite a major religious theme, is played through all sorts of comic possibilities where people lose their heads or get cut into bits.

Yeah, one thing that really struck me is how offhand his violence is; that pops up again in certain Oz books. People are run through grinders and it’s no big deal!

Yes, some of these surprises are sort of nasty – but you’re not quite supposed to see them that way.

I actually think the treatment of violence is relatively unique to Baum. Roald Dahl, for instance, plays with violence in a similarly casual way, but there’s always something mischievous or a bit sarcastic about it. Baum is sort of…magical-pragmatic about it, if you will. People lose limbs – and then they pick them up and put them back on. Bears are made into sausages and retain a measure of sentience. It’s all done in this, “Well, why not?” sort of tone, like a sort of narrative shrug. “Oh, yeah…I guess he did lose his head. Huh. Moving on now…”

I’d forgotten about the dancing bear sausages! I think the idea that they are still self-aware, even after they’ve been made into food, is the kind of thing even Dahl would hesitate to do. It suggests a complete breakdown in meaning and being that is actually quite disturbing if you linger on it.

I agree! But it’s very…non-nightmarish, just because of the way Baum describes it. He’s so straightforward. “Well, yeah, of course they still like to dance.” It slips by you as a child reader because he never dwells. It’s only as adult readers, I think, that we go, “Waitaminnit…”

Some of it really is genuinely funny, too. All the stuff about the king’s different new heads follows a wonderful magical logic that feels very Baum. There’s even some antecedent to the Tin Woodman in the king’s wooden head, I think.

Of course, it’s all in those fairy tales that are his source material. There’s definitely a talking sausage in Hans Christian Andersen, as well as a talking bean that gets over-excited and explodes. In Oscar Wilde, there is a rocket that is incredibly vain and literally goes off on one.

I don’t know my Andersen as well as I should (the only ones I know are the heavy hitters like Snow Queen and Little Mermaid), but my impression of both his and Wilde’s fairy tales is they’re so moralistic as to be, in many cases, depressing, or at least incredibly pious. Baum does not do that here, which I appreciate. I know I’m simplifying it, but he just seems to enjoy having fun. Once again, I get the impression of a man who told bedtime stories – and reveled in them.

Andersen and Wilde are both taking a new approach to the fairy tale as a literary form that is suddenly full of Christian mysticism and heavy morality, unlike, say, The Town Musicians of Bremen.

I think Baum’s just continuing the evolution of the fantasy story – away from Victorian morality and toward something distinctly American, as well as distinctly “of the new century.” It’s no accident, in my opinion, that something like The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is coming out of the turn-of-the-century American mid-west. This is an era of P.T. Barnum, of Harry Houdini, of Thomas Edison… We talked about it a little bit before, but I think Baum’s writing increasingly reflects this new culture. Part of that transition is the kind of trope-flipping you see starting to emerge in the Mo stories.

Right. It’s metropolitan and snappy. It’s moving folk culture into city culture.

Dot and Tot, on the other hand… Well, it’s less obvious what that book is trying to do. Cynically, part of me thinks it’s a simple cash-in on the success of Wizard. There are, actually, some good parts to it, but it just isn’t as inventive as Wizard or Mo, and it doesn’t hang together as a novel. At least, that’s my opinion.

Cynical or otherwise, though, I definitely get the impression in that Baum let Denslow pull his weight in Dot and Tot. I’m not sure if that’s laziness or just a simple admission that half of Wizard‘s success was Denslow’s design. I mean, why not try to repeat it?

Yours is an opinion that I share. The whole book actually has quite a heavily design-led construction, in that it’s sort of linear and symmetrical and quartered up.

Good point. I do think I missed something not reading an edition with Denslow’s design. I had to go back and look at a digital version for that. Admittedly, his duo-tone illustrations for the book are lovely. They make the whole thing more attractive. In contrast, the edition I read is the ’90s reprint with Donald Abbot’s illustrations. Abbot’s clearly talented, but his entire style is based on imitating Denslow. His illustrations for the book are fairly few in number and entirely black-and-white, so…what was the point? Why not reprint Denslow’s art, which is surely in the public domain?

Well, quite. I read the Project Gutenberg version and the simplicity of the story feels like it’s tailored for Denslow: lots of vignettes, odd conversations, and round things. In Wizard, you feel like they keep going off the beaten track and deviating from the path and getting lost in the woods and the flowers. Here it’s like progressing through a series of dioramas.

You know what I kept thinking of?

Giving up? Me too.

Ha! Well, besides that. I kept being reminded of old video games on Super Nintendo or Sega Genesis, “platformers” where you have different “worlds.” You know, one level might be an ice world, one level might be a jungle world… I can even think of one or two games where the player-controlled character hops from one magical island to another.

Oh yes! Gosh, the characters even look a bit like the Mario Brothers – and there’s a princess in the middle.

It’s so segmented, so episodic it almost hurts. I was struck by how easily you could lift whole sequences out; “The Watch-Dog of Merryland” actually was excerpted later, in one of the Reilly & Britton Baum readers for little kids. The whole sequence with the storks and the babies felt like it could be a very sweet picture book on its own.

Dot and Tot also reminded me of Winsor McKay’s Little Nemo comics, which would have been starting just a couple of years later. They are similarly fragmented, depending a lot on their art for their appeal. Clearly audiences of the time were okay with this type of brief fantasy vignette.

I think it’s interesting that in Wizard the journey is really quite arduous – there’s a lot of detail about how Dorothy gets tired and hungry every evening. I think we both singled out references to that in our chat about the book. Here, though, the protagonists just drift from place to place like holidaymakers on the It’s A Small World ride at Disneyland.

They’re just sightseers. They have no motivation; they don’t even paddle the boat, as far as I can remember. And apart from a very exciting bit at the middle of the book where it looks like something is going to happen, they change nothing at all.

That’s exactly right! They have an experience and then they go, “Well, that’s very nice, but we must be going.” There is, truly, no plot at all. Plus, there’s a very strange inversion with Wizard that this “Dot,” unlike the one from Kansas, is a massively entitled, spoiled little rich girl. Baum obviously figured out that approach doesn’t appeal to audiences, because he never (to my knowledge) used it again.

Worse, the working-class boy is a sub-human idiot grotesque. I mean, you’re supposed to like him – but in the way that you might come to like a dog, perhaps.

…And I’ve just choked on my coffee. Thanks for that, Nick, old sock. No, you’re absolutely right. Unfortunately, no one took Baum to one side and told him that Tot’s lisping slang is incredibly annoying; it’s going to return with a vengeance when he brings Dorothy – our Dorothy – back to Oz. Prepare yourself now.

I think Dot and Tot are emblematic of the struggle Baum had with his protagonists for the rest of his career. You can tell, in inventing characters like Betsy, Trot, and Cap’n Bill, that he knows his audience responds well to characters they relate with. Yet he just can’t resist taking these normal people and making them, basically, insanely rich royalty. That’s not just the Oz books, either – it’s a common theme in his pseudonymous adventure stories for boys and even the Aunt Jane’s Nieces stories for girls. He cannot resist giving these people fortunes.

The funny thing about all this is that it kind of makes sense to have a spoiled girl enter the book at the start, so long as she experiences some emotional epiphany halfway through. Dorothy doesn’t actually have any more character development than Dot, though – she’s just steadfast and tough throughout.

Even Dorothy eventually becomes a Poor Little Rich Girl in reverse: the next time we’ll meet her, she’ll be on a ship going to Australia. Where did Uncle Henry come up with that kind of money? Before long, Ozma basically sets her up in a palace! So much for “Home Again.”

The impression I usually get – and I think this is generally accurate – is that Baum himself came from the upper-middle-class, it’s just that at the time he wrote Wizard he was hurting for cash. Whenever Baum has money, he tends to very quickly give his protagonists money (or the equivalent of “riches,” anyway). Dot may very well be based on his own family – he certainly put her in Roselawn, which was his childhood home. For all we know, Baum was a spoiled little kid who befriended the gardener’s subhuman troll child. We’ll never know for sure. (Okay, I’m being facetious with that last bit.)

Well, he was an ill child, with some sort of heart condition, which is like Dot at the start of the novel. And didn’t his father set up a newspaper for him to run? There’s definitely something to what you’re suggesting, I think.

It’s obvious at this point that neither of us was terribly enamored of Dot and Tot of Merryland. I would say I found it readable, but it’s not a story I really want to read again, which is quite unusual for a Baum book.

What’s interesting to me is it’s one of the very rare Baum fantasies that hasn’t stayed in print at all. It looks like the last of the original publisher’s editions was printed in the 1920s – and then that’s pretty much it until a mid-’90s reprint by Emerald City Press. Unlike Mo, or Queen Zixi of Ix, or even American Fairy Tales, there’s no Dover paperback edition keeping it in print. So my question for you is this: does the book deserve to fade into obscurity?

I think you can probably give a better answer to this than I can, because I don’t know Zixi or American Fairy Tales, but I have to say, if any work of a great writer like Baum deserves obscurity – and we are so lucky to have things like Project Gutenberg, where if you really want to experience this book, including the Denslow illustrations, you can – I personally think this book has nothing to offer a casual reader. I thought it was dreadful for the most part, lazy and cliched and boring and stupid, and even worse for following a novel with lots of nuance and invention like Wizard. Just to be clear, mind you.

I’ll say one thing for Dot and Tot, though. I would really like to write a sequel to it.

What, really?

Really. Baum spends ages seemingly buildlng up this really exciting mix of sci-fi and horror and fantasy at the center of the book, with the tyrant and her “thinking machine” and the oppressed dolls. I really want to send Dorothy and Scraps and the Wogglebug into that scenario and find out what’s really going on there. If they can release the Watchdog and shove Dot out of her boat into the water, so much the better.

I can hear next year’s Oziana calling!

I was so convinced that something of the sort would actually happen in the novel itself – and then it just petered out. I feel like, at this point, Baum is attracted to really crazy, somewhat beautiful images but not necessarily interested in telling stories about them.

Unlike Dot and Tot, The Magical Monarch of Mo is still very much available as an illustrated paperback in this country, and you can pick up the Dover edition for cheap, too. Yours has 14 stories, right?

Yes – or rather, 14 surprises.

Quite. I ask mostly because I can’t find my old Dover paperback, and one or two of these stories felt absolutely unfamiliar to me.

It’s funny, I experienced much the same thing. I remembered them as much lighter and frothier.

I do know that the Dover uses the color plates from A New Wonderland, which was the original version of the book; there are more of them, and they’re printed in duo-tone. I don’t have as many in my Bobbs-Merrill Mo, but mine are in “full color,” if you will. It’s an interesting distinction.

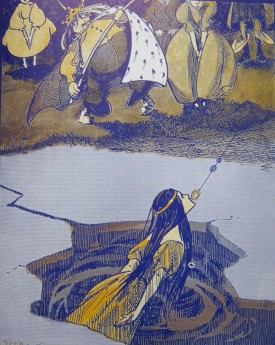

I think the two-color plates are nice; they have a sort of elegant, simplified art nouveau quality. I’m not quite so impressed by the majority of the illustrations. A lot of them feel rather thrown away and insubstantial compared to Denslow and Neill, but maybe they suit the more ephemeral style of the Mo stories.

I rather like them – despite Denslow’s obvious skill at design, I actually like these more romanticized figures better. The Purple Dragon is great, too. Still not as good as my beloved John R. Neill and his full-on art nouveau style, but quite pleasant, overall, and probably my favorite Baum illustrations by another artist. There’s a lot of really nice topsy-turvy imagery in the stories, and I think that’s reflected in the art.

So do we keep The Magical Monarch of Mo in print? Is it worth it?

I’m going to turn that question back on to you, Grand Inquisitor, and ask: if Mo is read today, who is its audience? Would you read it to a child? Do you think it was a good children’s book even in its day?

Well, I quite like the stories – and I quite liked them as a child, too, which probably proves something. Whether they have an audience today, however, I’m not entirely sure; I think if the Oz books appeal to a child, it’s fairly likely Mo will, too, even though the stories are considerably more bitty. If anything, the stories are more child-friendly now than they were 25 years ago, when I first read them; young kids are exposed to so much more violence now on a regular basis.

A while ago, you sent me this piece about a Magical Monarch of Mo sitcom starring Groucho Marx, where he’s an ordinary guy daydreaming about a crazy fantasy world. I see a lot of Tom and Jerry and even Ren and Stimpy in these stories, and I wonder whether some of them might make really good TV cartoons.

I had a similar thought, actually. I found myself wondering why they’d never been adapted, unlike so much of the rest of Baum’s output. They do feel more than a bit like Looney Tunes.

Is that an American tradition, perhaps? That kind of manic violence where people knock each other down and then get up and go home?

Yeah, I suppose it is, really. That’s all The Three Stooges was, in a nutshell, and you see it in film comedies from Buster Keaton to Jim Carrey to The Hangover and on up. You have a physical comedy history in Britain, too, but it’s rather less about the theater of physical pain. Noel Coward we are not, I’m afraid – even the 1902 stage Wizard of Oz has comedy violence in the “Football” song, which I believe was originally performed with the football made to look like the Scarecrow’s head.

I must say, I find it sort of bizarre that there was such a long gap between Wizard and The Marvelous Land of Oz, even allowing for Dot and Tot and a marvelous reprint of Mo. You’ve just reminded me, though: he was a little bit busy with this thing called a major stage musical!

As it happens, Nick, that’s an excellent place to stop and come back later. Soon, we’ll be examining Mr. Baum’s attempt to catch theatrical lightning in a bottle twice – or as most people know it, the second Oz book…

Next Time

THE MARVELOUS LAND OF OZ

Read along with us and send in your thoughts! Tell us what topics we should discuss! Be a part of BURZEE!

Books of Wonder would have had to spend more money than deemed necessary to do a decent looking photo-offset reprinting of DOT & TOT. Plus, the racial caricatures would have been problematic.

LikeLike

Good point. I admit I was thinking more about Dover Publications, who put out paperback versions of about half a dozen of Baum’s non-Oz fantasies, as well as coloring books, stickers, royalty-free clipart, and more based on Denslow’s “Wizard” illustrations. “Dot and Tot” seemed like something fairly obvious for them. Of course, they may have simply realized it wasn’t very good…

LikeLike

Dover’s output was somewhat erratic. Aside from Wizard and Land they also published Mo, Ix, John Dough, American Fairy Tales, Santa Claus and Master Key from 1968 to 1977. They let John Dough and Master Key go out of print in the early 1980s. Thereafter they reprinted the Oz and Trot books from 1984 until 2002. They seemed to have considered Yew around 1990, but apparently decided against it. Aside from literary quality, the illustrations probably didn’t reproduce well in half tone and wasn’t worth using color.

LikeLike

Dover’s output was somewhat erratic. Aside from Wizard and Land they also published Mo, Ix, John Dough, American Fairy Tales, Santa Claus and Master Key from 1968 to 1977. They let John Dough and Master Key go out of print in the early 1980s. Thereafter they reprinted the Oz and Trot books from 1984 until 2002. They seemed to have considered Yew around 1990, but apparently decided against it. Aside from literary quality, the illustrations probably didn’t reproduce well in half tone and wasn’t worth using color.

LikeLike

Thanks for this! I laughed aloud at the discussion of violence in these stories. There is a sort of matter-of-factness about violence in Baum that stops it from being disturbing; one of the most interesting things about the Shanower/Young comics, I think, is how they manage to be much more violent without actually changing the text!

I haven’t read these books in a long time, but my memories are much less nostalgic than those of some others of Baum’s non-Oz fantasies (I really enjoyed The Master Key as a kid, for example).

LikeLike

And thank you for your comment, Steve! We’ll be talking about the Shanower/Young comics in a future post, and yes, they certainly are full of frenetic and over-the-top action, aren’t they? We both think they’re brilliant!

LikeLike

I’d love to read The Master Key at some point, too. Ever since I was a kid it sounded so cool! But we must be careful or we’ll never reach Ruth Plumly-Thompson before we’re old and grey and our evil alien overlords have banned reading…

LikeLike