By 1909, L. Frank Baum was ready to move on from Oz. He had hinted as much in the author’s note to his last book, Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz, and the note that opened his new offering, The Road to Oz, made it explicit: “I have received some very remarkable News from the Land of Oz, which has greatly astonished me . . . but it is a such a long and exciting story that it must be saved for another book – and perhaps that book will be the last story that is ever told about the Land of Oz.” In the meantime, Baum offered up another story that was both lighter and frothier than its predecessor, built almost solely around the journey through fairyland that formed the core of many of his earlier tales. In it, he said, he tried to “respect the wishes” of his young readers and provide them with “some new characters . . . that ought to win [their] love.” It’s hard not to read those as the vague, upbeat sentiments of a man who feels worn down.

By 1909, L. Frank Baum was ready to move on from Oz. He had hinted as much in the author’s note to his last book, Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz, and the note that opened his new offering, The Road to Oz, made it explicit: “I have received some very remarkable News from the Land of Oz, which has greatly astonished me . . . but it is a such a long and exciting story that it must be saved for another book – and perhaps that book will be the last story that is ever told about the Land of Oz.” In the meantime, Baum offered up another story that was both lighter and frothier than its predecessor, built almost solely around the journey through fairyland that formed the core of many of his earlier tales. In it, he said, he tried to “respect the wishes” of his young readers and provide them with “some new characters . . . that ought to win [their] love.” It’s hard not to read those as the vague, upbeat sentiments of a man who feels worn down.

Here at BURZEE, though, we are anything but worn down. A year has passed since our very first blog, and we’re really in the groove of it now. After a few slow starts, we’re feeling confident in our format and excited for the books to come. We’d like to thank you for coming along with us! Now, it’s time to celebrate: surprisingly, and by total coincidence, with a book that ends in a party – the blog comes full circle with a visit from the magical and immortal Santa Claus . . .

I actually came to this book with very minimal expectations, says Nick. My only real memory of this book is a very clear image of being read it by my Mum. Everything about the memory is odd – furniture in the wrong places, and so on – so I wonder if this was around the time my sister was born, when I was five. Oddly enough, I still remember key points, like Button Bright’s facial reconstruction and the fate of the Love Magnet, but I was only vaguely aware, before reading it again, that the novel itself was a little slow. What were your memories and expectations, Sarah?

I actually came to this book with very minimal expectations, says Nick. My only real memory of this book is a very clear image of being read it by my Mum. Everything about the memory is odd – furniture in the wrong places, and so on – so I wonder if this was around the time my sister was born, when I was five. Oddly enough, I still remember key points, like Button Bright’s facial reconstruction and the fate of the Love Magnet, but I was only vaguely aware, before reading it again, that the novel itself was a little slow. What were your memories and expectations, Sarah?

I don’t have a strong memory of my opinion of this book, Sarah replies, except that I always lumped it in with Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz as one of the lesser Baum books. I think that’s just because of its relatively minimal narrative drive.

Let’s start with that, then, because I’d actually call it total lack of narrative drive. I was surprised, in virtually every chapter, by the wealth of things that do not happen and obstacles that fail to arise (or persist). After a book where characters were being chucked down pits or attacked by monsters every few pages, I almost couldn’t believe what I was reading. It’s a travelogue, essentially.

Honestly, I felt like the first few chapters of the book worked pretty well. I like that Baum has given up on the “extreme weather” device of sending Dorothy to Oz, and instead, there’s the strong visual of her surrounded by endless roads; you can absolutely visualize how the cinematic version of that scene would look. The tone of the first few chapters works well, too. The trouble is that after you meet the last member of Dorothy’s company, there’s almost no danger whatsoever, and Baum starts to repeat himself almost immediately.

Honestly, I felt like the first few chapters of the book worked pretty well. I like that Baum has given up on the “extreme weather” device of sending Dorothy to Oz, and instead, there’s the strong visual of her surrounded by endless roads; you can absolutely visualize how the cinematic version of that scene would look. The tone of the first few chapters works well, too. The trouble is that after you meet the last member of Dorothy’s company, there’s almost no danger whatsoever, and Baum starts to repeat himself almost immediately.

Unlike in Wonderful Wizard, there’s nothing personally at stake for the characters –particularly Dorothy, who is so confident about reaching the safety of Ozma so early on and keeps reassuring the other characters. They are so lacking in personal motivation themselves that there really isn’t anything for them to worry about, up to and including unexpectedly having animal heads.

Yes – they get concerned for a moment, and then it’s over. It’s too bad, because in most regards, I think this is actually a fairly strong set of diverse characters. The problem is that everyone happily decides go along with whatever happens, which does not make for an exciting story. Reading the two books right after another, I think I ended up with a hazy idea that if you combined the characters of Road and the incidents of Dorothy and the Wizard, you would end up with one really good movie. That pretty clearly indicates the deficiencies of both books.

The significant improvement on the last book is in the characters, definitely, which brings us back to one of Baum’s great strengths. Even though they have nothing to lose and even less to contribute, all the central characters here are really enjoyable. You want to spend time with them.

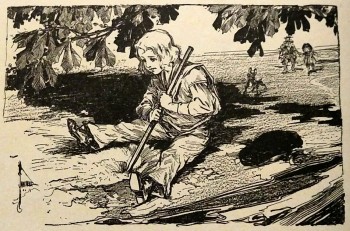

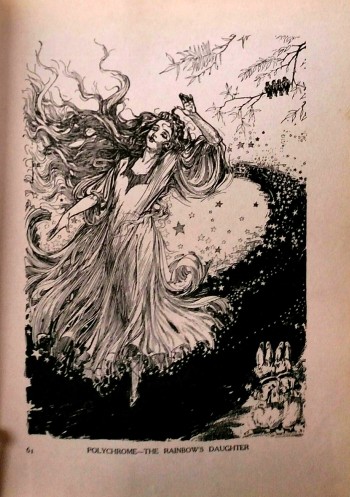

Right. There’s no “Zeb”-type here; nobody’s here just for their brute strength. Button-Bright is effectively useless, but he’s a realistic small boy who feels drawn from life, as if he was a child that Baum knew – maybe even once of his own sons. Polychrome doesn’t contribute a whole lot to the plot, but she’s a great character in that she’s so dainty and ephemeral, especially alongside the very grounded personality of Dorothy. It should be noted that Baum obviously liked these characters, too: he featured all of them as protagonists again, more than once!

It’s the combination of their differences that really works. Polychrome is so fluffy and Dorothy so down to earth; Button Bright so innocent and the Shaggy Man so worldly. The fact that there’s no hierarchy between them brings us back to what I think of as a sort of Muppet Show aesthetic: it shouldn’t work to have these characters together, but they form an entertaining gang, for all their extreme contrasts.

I think that’s an interesting point; essentially what Baum says again and again – at least, in his best combinations of characters – is that we’re all weirdos and that’s okay, which is surely a very Muppet Show idea. The scene that demonstrates that best is a great one in Dunkiton where everybody is given what they like best for dinner. The Shaggy Man is a man of the road, and he wants something portable and practical: a ham sandwich and an apple. Polychrome, meanwhile, has three dew drops on a plate. Button Bright, being a child, just wants pie, and Dorothy… I really liked Dorothy’s choice. Any other author would have given Dorothy something delicate and feminine and a little bit proper, like a fruit salad or a dish of ice cream, but Baum has her ask for a steak and some chocolate layer cake! It’s the most red-blooded American meal there could possibly be, and then – ever the good-hearted child – she shares some of the steak with Toto. That little scene alone shows you these characters in counterpoint to each other in a way that makes them feel vivid and alive.

Picking up on your point, there’s actually a scene near the end where they arrive in Oz, something of a repeat of that bit in Dorothy and the Wizard where everybody meets one another and tells their life stories. Here, they tell their life stories again – including Dorothy and the Wizard! – which is sort of funny and endless. Polychrome says (echoing Billina in Ozma of Oz), “You have some queer friends, Dorothy,” and Dorothy says, “The queerness doesn’t matter so long as they are friends.” That could almost be the motto of the entire Oz series.

King of the Road

Of course, not all of Baum’s homilies are so sentimental. Another striking one concerns Tik-Tok: “Perhaps it is better to be a machine that does its duty than a flesh-and-blood person who will not, for a dead truth is better than a live falsehood.” Reading between the lines, I think Baum resented being penned into writing endless sequels, but it’s still a very sincere and even personal novel.

That’s perhaps nowhere more evident than in the character of the Shaggy Man. In the Winter 1990 issue of The Baum Bugle, there’s a short piece by Hal Lynch calling this “the most dangerous Oz book.” Lynch rails against the idea that Baum starts a novel where Dorothy goes off with a strange man, saying that the most sacred rule of childhood has been violated: don’t go off with strangers. While I certainly take his point, the idea that you wouldn’t trust someone because you don’t know them yet is pretty much against everything Baum says in his books. The way a Baum story works, of course the Shaggy Man is somebody who is trustworthy, of course he turns out not to be a villain.

I wonder if there is any significance to be drawn from the fact that the Shaggy Man repeatedly refers to Dorothy as “my dear,” exactly how Baum refers to his readers. I’m not saying that’s deliberate insertion of Baum into this novel, but I do think there’s a real identification between Baum and the Shaggy Man, particularly in his relationship to trusting children like Dorothy. He’s not just romanticized; I feel that he is a figure of personal significance to Baum.

Sure. I also found myself wondering if there’s a little bit of Baum in the Shaggy Man, just the way that there’s a little bit of Baum in the Wizard: they’re both self-made men (well, to a point), and they’re both tricksters. I wonder if Baum at all styled himself as the Shaggy Man in that in 1909, he had travelled so much over the past few years.

All that said, at this point, Baum also functions as the opposite of the Shaggy Man. He has so many commitments at the time this comes out – even grandchildren! The Shaggy Man represents a freedom about which a man like Frank Baum can only fantasize.

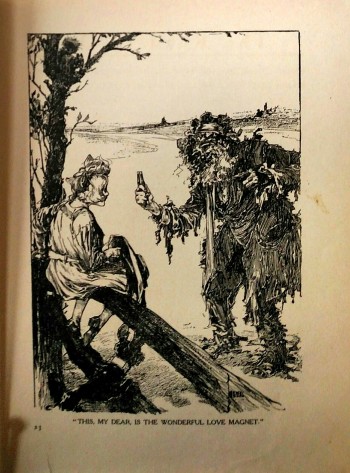

How do you feel about the Love Magnet? For me, it’s the one really dark thing in this book. I don’t mean scary – because the encounter with the Scoodlers is certainly that – I mean dark. Manipulation isn’t something that Baum tends to ascribe to positive characters. The Wizard was manipulative in his first appearance, and so was the Nome King; here, we have the major adult figure of the book manipulating the affections of child protagonists. That’s a fairly dangerous item.

Actually, I didn’t read any of those sinister overtones this time. In fact, I saw the Love Magnet as a rather melancholy object, perhaps even meant as an indictment of our own world, where someone like the Shaggy Man is going to be intrinsically unloved. Bearing in mind the possibility that Baum saw himself in the figure of the Shaggy Man, I couldn’t help wondering if the love magnet was symbolic of the Oz books themselves (my dears). It’s an object that wins him the love and admiration of many, but it’s artificial and it’s stolen, and to a great extent it’s even tawdry.

We’re returning to that idea of the most dangerous Oz book, I feel. It’s much less concerning to me that Dorothy goes off with a stranger, particularly in the context of 1909, than it is that Dorothy goes away with someone who is manipulating her.

What’s funny is that you can imagine the feedback coming in for Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz: “Too much drama! Too scary!” The Love Magnet is a sort of guarantee, from the very first chapter, that our heroes will survive any dangerous situation; everyone will love them instead of trying to destroy them. The more you think of it, though, the more you realize how much Baum plays on this device – this artificial rosy glow. In the cities of Foxville or Dunkiton, people love our characters so much they want to remake them in their own image. It goes so far in the land of the Scoodlers that this symbol of love – this “safety guarantee” on the very narrative of the book – becomes comically inverted to the point of horror.

That’s a particularly funny moment. There might actually be a little bit of warning here, too, which is that you can’t force people to love you. The Scoodlers do say, “We love you!” but it’s “We love you in soup!”

Behave Yourself!

I found it very enjoyable that, once again, we follow Dorothy on a simple, straightforward journey, just as in the very first Oz book. Dorothy and Toto, in fact. How nice is it to have Toto back? I’ve noticed that Baum anthropomorphizes all of his cats; whether they’re the Lion, the Tiger, or even Eureka, they’re all very human in their personalities. Toto, on the other hand, is a dog. Toto is the most doggish dog there could possibly be, and Baum writes him with the enthusiasm of someone who knows and enjoys dogs. Toto’s entire first scene in this book has the joyful glee of a dog’s irreverent behaviour and the sheer fun of chaos they bring to a situation. I, for one, enjoyed having Toto back with Dorothy as opposed to other, prissier companions.

I almost feel that Toto functions as the id to Dorothy’s ego. She’s the one saying, “We don’t do that, we’re well behaved,” and he just hares off after everything, barks at everyone, and openly shows his affection whenever he wants. In the banquet at the end, the animals dine with the people and Toto is actually in a highchair with a bib. There’s a line about how in Oz, animals are treated just the same as anyone, as long as they behave themselves.

In future books, Ozma will actually give that as her sole edict: the only rule in Oz is to “behave yourself.”

We don’t get that here, but we do learn that nobody dies in Oz except people who do bad things and are put to death. That’s a strong incentive to behave yourself! To me, Baum is working through a process in these early novels of solidifying and stabilizing Oz, getting it to where everything is such a perfect utopia, he couldn’t write another sequel if they beg him. Part of that involves a real moral absolutism, which is casually mentioned and lightly sketched but is, in fact, totally extreme. In the merry old land of Oz, if you don’t “behave,” you are as good as rejecting eternal life in paradise.

Yes – and a paradise without any money, too. Baum is quietly redefining Oz as a socialist utopia, which is interesting because it changes Oz from being somewhere you would like to visit but never live in to somewhere you would never leave.

It’s funny that in the opening book there was a gleeful note in the idea that “Oz has never been civilized,” but since Ozma came in, it’s less anarchic, more civilized and more morally authoritarian than ever before.

We’ve seen a few examples of Ozma’s style of governance by now. I think as a child I found it standard and very natural, but as an adult, I worry a bit more about what having Ozma as my ruler would be like.

It’s interesting to me that it is a socialist utopia in the vein of William Morris’ quietly radical novel News from Nowhere, but it still has an unelected, hereditary monarch. Everyone’s throwing roses at her feet, and she lives in a palace with a window to anywhere in Oz. There’s this weird sense of stasis, too, with these new ideas about (a lack of) death. Again, we’re getting to a point where Baum can leave things and we’ll all trust that they go on forever: we’re moving towards an eternal summer and an eternal reign of Ozma. As a child that’s reassuring, but for an adult, it’s the opposite.

It makes Ozma’s rule feel like a benevolent dictatorship; it’s hard not to be reminded of Fidel Castro, who died just before we had this conversation. How much do tyrants freeze their countries in time, ultimately to the detriment of their people? What’s troubling for us is that in earlier books we’ve seen Oz as a much more complex place, where citizens are clearly being taken advantage of by governments, where certain members of the population have attempted to revolt. Now we’re being asked to accept that everybody is just fine with Ozma’s complete and unending oversight. Those two scenarios don’t gel very well, in my opinion.

I think it doesn’t help that at this point in the series, Ozma is kind of unknowable. Ever since she changed from a boy into a girl we’ve seen less and less of her. She’s a slightly faceless figure in the text. It’s only really in Neill’s illustrations that she becomes a person with a character.

It’s hard for me to separate, sometimes, because I’ve read the later Oz books and I know Ozma quite well. (In some of those, she becomes far more of a protagonist than we’ve yet seen.) Dorothy, however, already seems to know how great Ozma is: her gushing descriptions clearly make her out to be the new ruler’s biggest fan.

Dorothy’s love for Ozma is also emphasized by the illustrations. There’s a lovely picture of the girls sharing a chaste kiss, and the same image is essentially emblematized on the back cover. It’s almost as if this quasi-romantic love between the earthly farmgirl and her fantastical girlfriend represent the very character of the Oz books, where the down-to-earth meets the far-fetched. Perhaps for Neill that is more romantic, and for Baum it’s more childlike?

I think it’s clear – from, at least, Neill’s illustrations in this book and the previous one – that Ozma and Dorothy have what would have been called, at the turn of the century, a “romantic friendship.” It’s the kind of thing you see exemplified in books such as Anne of Green Gables, where Anne and Diana gush about one another endlessly and, even when they go off to be married, openly devote themselves to one another for the Remainder of Recorded Time. It’s something alien to our more sexually oriented mindset these days. No matter how you look at it, though, I can’t but think that Dorothy is influenced by her obvious love for the Princess Ozma, and as an adult it makes me wonder if she sees Ozma entirely clearly.

You mean that she sees her, perhaps, as a child as opposed to a head of state with all of the other, slightly worrying aspects you’ve described?

Well, I wonder if Dorothy sees Ozma as a much more innocent figure than she really may be. That isn’t helped by the fact that in later books Baum will play with how old Ozma is, and how much magical power she has. I have to question whether Ozma is simply a naïve but benevolent leader or whether she, like the Shaggy Man, is much more manipulative than Dorothy gives her credit. Even something as simple as Ozma having a giant birthday party gets called into question. As adults, we have to wonder if this is a child having the most outrageous birthday party ever or a queen who wants her courtiers to bow and scrape in an outrageous expression of ceremony.

For She’s a Jolly Good Fellow(?)

Potentially, it’s also a demonstration of statesmanship between the new ruler of Oz and, say, the Queen of Merryland or King John Dough. I must say that the cameos at the birthday party were a particular pleasure for me, having read and discussed all these books for the first time with you this year. All the awkwardness and oddness of those books has paid off in the uniquely weird joy of seeing all their protagonists sit down to dinner together at the end.

Ah, and now you see the endgame to my cunning plan! Even I hadn’t read all of those other books when we started out a year ago, and I was always intrigued with the way Baum included the characters at the end of this book. What I realize now is how obvious his motive was: he was getting children to ask their parents to buy those books for Christmas, probably because they weren’t selling as well!

I’m so naïve that I didn’t spot that until afterward. Of course, it makes perfect sense, along with the “please read my other books, and by the way I’m ending the series next year” message that we get in the preface. What’s beautiful, though, is that I didn’t notice what was going on; these books are precisely the kind of place where you would have Santa Claus turn up at Ozma’s birthday party.

I think, inadvertently, Baum has just made his world much bigger and brighter because he’s linked all these stories together. Oz isn’t just one little place in the middle of nowhere anymore; it’s alongside the borders of all of these other countries. I think that’s enough to send any child’s head spinning with possibility, and it frees Baum up to do more of that in the future – which he will, of course.

Even the Braided Man turns up to say –

“Buy Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz, kids!”

“Find out who this completely bizarre character is…”

“… for the three pages in which he appears.” Yep!

All the Colors of the Rainbow

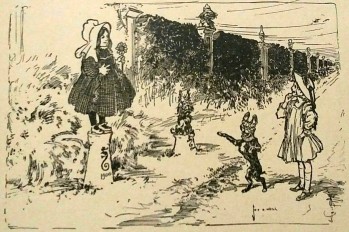

This is a good place to talk about the John R. Neill illustrations. Although he’s depicted the John Dough and the Cherub characters before, he’s never drawn Queen Zixi of Ix – who looks very different from the version in her own book – or the Queen of Merryland or the Candy Man. I think this book is probably the candidate for Neill’s most delicate artwork. It’s very careful, it’s very layered, and it’s almost impossible to see at any detail if you reduce it to a smaller size. It’s very, very beautiful. At the same time, though, I have to be incredibly regretful that this is the one Baum book for which Neill provided no colour plates. Unlike the previous book, I think this one would have really benefited from some watercolors.

When you literally have the Rainbow’s Daughter in a book it would be nice to have her in color.

When she pops up again in a few books’ time she is very colorful indeed. Wouldn’t it be great to see the attack of the Scoodlers in color, too?

…Or Foxville, because they’re such fops and dandies, aren’t they? That would look wonderful.

…Or the sailing of Johnny Dooit’s ship across the Deadly Desert, which seems to have inspired a number of cover artists. Michael Herring, for instance, used it on the cover of the Del Rey paperback.

It’s one of those books that has such incredible imagery – more than earlier Baum stuff, perhaps. Not much happens, but what does happen is unlike anything else. I must say, having looked around online, I wish I had a copy of the Little Golden Book. The artwork there is so charming and full of life, and there’s a great image of the desert ship in there full of pure joie de vivre.

How do you feel about the colored pages? (The earliest editions of The Road to Oz were published with subsequent sections of the book printed on different colored page stock, including tan, lilac, blue, orange, green and brown. All of the Neill illustrations in this blog are sampled from the first edition, first printing of the book.) In my opinion, they’re a neat effect, but I don’t think they do anything particularly useful.

Well, from the outside of the book they look great, but I don’t think they ever make Neill’s art look better than it would on white paper. Sometimes I think it’s the reverse, and the detail is not very clearly differentiated. There are some cases where it’s hard to make out what’s going on – like the image of Santa Claus in the bubble, where it’s hard to tell it’s Santa at all.

Part of that’s not having any color, which is improved, at least somewhat, in the 1939 “junior edition” of The Road to Oz. That reduced-size release “for little hands” colored some of Neill’s illustrations to accompany an abridged version of the story. Even there, though, I think any sort of reproduction of Neill’s pictures makes the quality slightly worse. The illustrations for this book are very delicate because they’re made up of so many fine lines.

The crowd scenes are incredible. Baum basically says, would you please draw a crowd of two hundred people, made up of scarecrows, animals, robots and giant insects, and Neill just delivers.

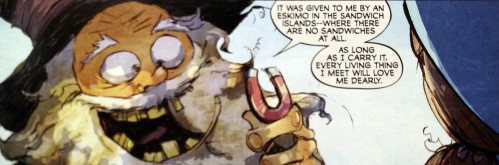

Throughout our blogs, I’ve been trying to find artists other than Neill to showcase – not because I dislike Neill (far from it), but because I’m aware of how much he owns the identity of so many of these characters from The Marvelous Land of Oz onward. In fact, he basically owns the illustrated Oz of the 20th century: although he died in the 1940s, his designs for the characters lived on through the work of prominent Oz artists Dick Martin (in the ‘60s and ‘70s) and Eric Shanower (in the ‘80s and ‘90s), both of whom intentionally drew in a style inspired by Neill. That means that for almost 100 years, the basic images of all the Oz characters have never really changed.

It’s only with Skottie Young, who did the Marvel Comics adaptations of the first six books, that I think time has finally moved on. I think Young is the significant Oz illustrator for the 2000s to date, and it’s with The Road to Oz, specifically, that I realise how much Young has left Neill behind. There’s no character who is more different and original than Young’s Polychrome. While on the one hand that’s a little bit heartbreaking for me – after all, the Oz in my head is and always will be John R. Neill’s – it’s also tremendously exciting to see Young so deftly demonstrate that there are still new approaches to take with these stories and characters.

An Experiment in Sweetness

I said before that my expectations were low for The Road to Oz because I knew that nothing of any note was going to happen; in fact, even less happens than I was expecting. I still really enjoyed the book, and every time I came back to it, I got something out of it. It’s so interesting to see references to books like Dot and Tot of Merryland, where Baum seemed to be experimenting with style and content, because he’s doing it again. It’s almost as if, like the rest of us, Baum just can’t figure out whether The Wonderful Wizard of Oz was mostly frightening or mostly reassuring. This time around, the Oz books are suddenly gentle and sweet and funny.

I think I was particularly not looking forward to it. I knew it was not one of my favorite Oz books as a child, and I had also heard other people say they gave up specifically on this book when they tried to read the Oz books in order. I knew, then, that this was not going to be an intrinsically great book, but I will say that I enjoyed reading it – and I think I enjoyed it more than Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz, too. It certainly sags in the middle, around the time they get to the Emerald City, but it’s very far from being a bad book. There are simply too many interesting characters and too many clever little moments for me to entirely give up on it.

And would you give this book to a child?

Yes, but for an entirely different reason to last time, which is that I think most children will enjoy these characters and enjoy these jokes. What concerns me is the final half or so of the book is so based in your knowing and wanting to know the existing characters of this series that it might not make a good introduction to the world. (Several notable fans, however – including Eric Shanower – clearly disagree!)

It doesn’t work as an introduction, no, but for my part, I still cherish that childhood memory of being read the book. Of the first five so far, it’s in this one that Baum has hit on the same voice as that of Wonderful Wizard.

I agree with you, Nick – but we can’t get too comfortable. In the next book, everything changes…

Do you love The Road to Oz, or do you long for a more exciting Oz tale? Tell us in a comment!

Next Time

THE EMERALD CITY OF OZ

THE EMERALD CITY OF OZ

Read along with us and send in your thoughts! Tell us what topics we should discuss! Be a part of BURZEE!

As always I love your commentary, which gives me much food for thought. Ozma as a dictator, the subtext of same sex love with Dorothy and Ozma, the effects of Baum’s dissatisfaction with the Oz books affecting the story, the creepiness of the love magnet, it all does add layers of meaning to the book. I always enjoyed this one, but it is a cozy travelogue. I agree that the characters are really what make the story.

I agree that Neill’s art is how I picture Oz but new imaginings like Scotty Young’s wonderful interpretations breathe new life into the stories.

LikeLike

When I read the Shanower/Young version of ROAD a couple months, I was amazed at how little I remembered– it’s definitely the one of the first six I remembered the least about, none of the encounters Dorothy and company had on the road were more than vaguely familiar, whereas I remembered many of the encounters in DOROTHY AND THE WIZARD.

My childhood editions of the Baum Oz novels are a bit of a mish-mash: Dovers, Books of Wonder, Del Reys. I had three Puffin Classics: MARVELLOUS LAND, ROAD, and TIK-TOK. LAND has very few illustrations, and if I remember correctly, ROAD (and TIK-TOK) has none! I’m starting to wonder to what extent my impression of an Oz novel’s quality correlates to the quality of illustration– my two favorites are DOROTHY AND THE WIZARD and PATCHWORK GIRL, both of which where Dover editions, which included the color plates and stuff, whereas many of the ones I have as Del Rey editions (with all the illustrations, but no color) I perceive as being middle-of-the-road.

LikeLike

I’ve said for a long time that the strongest aspect of the text of The Road to Oz is that the main characters are more themselves in this book than they ever were previously or ever were again. Delighted to find that you both seem to have decided along very similar lines.

Of course, the other strong aspect of the book is Neill’s illustrations. It’s difficult to imagine a first encounter with this story sans Neill’s pictures. I think the quality of the illustrations for The Road to Oz certainly elevates the quality of the book as a whole and is responsible for a great percentage of the enjoyment it provides readers. The Road to Oz was the first unabridged Oz book I experienced. I don’t know whether I would have been propelled into wanting to experience more of Oz without the illustrations.

LikeLike

I have trouble envisioning being introduced to any of Baum’s sequel Oz books the first time without Neill’s illustrations, so I hear you. Nick’s situation of growing up with them unillustrated leaves me both perplexed and a little…I don’t know…anxious? Oz books beg to be illustrated!

LikeLike