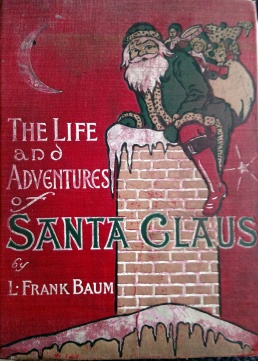

We decided to start our project by jumping a little bit ahead to Baum’s 1902 fantasy, The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus. For one thing, it was a seasonal choice – we would be reading it at the end of December – and for two, Sarah felt that it provided the backbone to much of Baum’s fantastical world-building. Plus, it wasn’t the obvious choice. And Nick had never read it before…

But first, a brief summary.

In the forest of Burzee, where the Immortals live, a human child is found by the Master Woodsman Ak and raised by the nymph Necile. Named “Claus,” or Little One, he grows to realize that he comes from mortal men, and he leaves Burzee to try and do some good in the time allotted him. Though thwarted by the villainous Awgwas, he helps and becomes a friend to all the local children, crafting them toys and eventually establishing traditions now attributed to Santa Claus. In time, though, he comes to his deathbed, and Ak is forced to call on the Council of Immortals to grant Claus the Mantle of Immortality so he may continue his good work.

In the forest of Burzee, where the Immortals live, a human child is found by the Master Woodsman Ak and raised by the nymph Necile. Named “Claus,” or Little One, he grows to realize that he comes from mortal men, and he leaves Burzee to try and do some good in the time allotted him. Though thwarted by the villainous Awgwas, he helps and becomes a friend to all the local children, crafting them toys and eventually establishing traditions now attributed to Santa Claus. In time, though, he comes to his deathbed, and Ak is forced to call on the Council of Immortals to grant Claus the Mantle of Immortality so he may continue his good work.

So! says Nick, I had really wanted to have this discussion at midnight on Christmas Eve – when people all over the world (or at least Great Britain) are breathlessly trying to sleep in order to allow a certain jolly chap in red fantastical egress to their house. At one point I was in that number too – were you also encouraged to believe in Father Christmas?

So! says Nick, I had really wanted to have this discussion at midnight on Christmas Eve – when people all over the world (or at least Great Britain) are breathlessly trying to sleep in order to allow a certain jolly chap in red fantastical egress to their house. At one point I was in that number too – were you also encouraged to believe in Father Christmas?

Oh yes, says Sarah, of course I was encouraged to believe in the Big Man. We don’t call him Father Christmas in the United States, naturally. But there was always a slightly winking, tongue-in-cheek quality to it… I think I knew by five or six years old that he was “real” but not “true,” if you know what I mean.

I have my own personal theory – because I don’t remember finding out the truth at one specific time – that it’s fantasies like The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus that help children process the idea of Father Christmas as a fiction. I remember enjoying writing my own silly stories about him, for instance, lighting the Northern Lights like candles.

I…did not do that, at least not that I remember. But I also think I was quite a cynical child, reasonably early on. I was very willing to suspend my disbelief and play the game – I’ve always been like that, I have a very high tolerance for nearly any sort of fantasy or imaginative play – but I do think I was fairly quickly aware it was a game, even if it wasn’t totally spelled out for me. Do you know what I mean?

I…did not do that, at least not that I remember. But I also think I was quite a cynical child, reasonably early on. I was very willing to suspend my disbelief and play the game – I’ve always been like that, I have a very high tolerance for nearly any sort of fantasy or imaginative play – but I do think I was fairly quickly aware it was a game, even if it wasn’t totally spelled out for me. Do you know what I mean?

Yes. Did you read The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus as a child? Did it influence the way you think of Santa Claus?

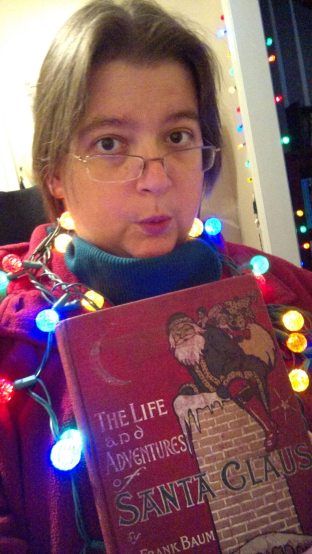

I definitely read it – I have my childhood copy here, in fact. I don’t think it really influenced me, though. I was never really a child who loved fairy tales – I mean, I read them, I liked them, but they weren’t anything I responded to emotionally – but I was getting very, very heavily into Greek and Egyptian myths around this age, so I treated the book in very much the same way. It’s a piece of mythology. It explains things you have no natural answer for, exactly the way myths and legends do, in an entertaining way that is far from guaranteed to be accurate.

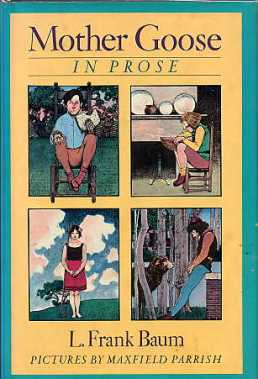

That leads very naturally into a question I have for you. We kicked this whole project off, in a somewhat low-key manner, by reading Mother Goose in Prose, Baum’s first published fantasy work (1897). And I know neither of us liked those stories very much; some of them were rather didactic, and their reason for existence seemed simply to function as “explanations” of the famous nursery rhymes. I kind of set us up intentionally, because Santa Claus functions in a very similar way: it’s a giant explanation, beat by beat, of all the familiar Santa Claus motifs and details – why he makes toys, why he uses a sleigh, where he got the reindeer, etc. It’s also quite moralistic, far more so than most later Baum books. But I still found I enjoyed it tremendously more than Mother Goose. What about you?

That leads very naturally into a question I have for you. We kicked this whole project off, in a somewhat low-key manner, by reading Mother Goose in Prose, Baum’s first published fantasy work (1897). And I know neither of us liked those stories very much; some of them were rather didactic, and their reason for existence seemed simply to function as “explanations” of the famous nursery rhymes. I kind of set us up intentionally, because Santa Claus functions in a very similar way: it’s a giant explanation, beat by beat, of all the familiar Santa Claus motifs and details – why he makes toys, why he uses a sleigh, where he got the reindeer, etc. It’s also quite moralistic, far more so than most later Baum books. But I still found I enjoyed it tremendously more than Mother Goose. What about you?

I didn’t think much of Mother Goose, it’s true. I think if you’re reducing the cow jumping over the moon to an optical illusion, you should hand in your pen. I guess the Baum of Mother Goose feels part of a joyless, bloodless brigade of writers – in the line of Anna Barbauld and Maria Edgeworth – who actively disapprove of whatever special quality fantasy has. He doesn’t subvert fantasy or play against it, he just encourages cynicism in his readers – and not with a laugh, either. I mean, where does a book like Mother Goose leave a child?

The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus is almost of the same ilk in that its treatment of fantasy, though semi-mystical, is so venerable and austere that we are never allowed to be seduced by it. You can’t quite believe in Burzee and its pious fairy folk. And there is so much explanation that the imagination is never tantalised or prompted as the fantastic usually does. In an ideal world, though, I’d put a bit of both books in a Christmassy fruitcake – the roughness and irreverence in the characters of Mother Goose and the high fantasy of Burzee. Potentially I’d really like the man who was Claus to be more like the roguish King Cole.

The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus is almost of the same ilk in that its treatment of fantasy, though semi-mystical, is so venerable and austere that we are never allowed to be seduced by it. You can’t quite believe in Burzee and its pious fairy folk. And there is so much explanation that the imagination is never tantalised or prompted as the fantastic usually does. In an ideal world, though, I’d put a bit of both books in a Christmassy fruitcake – the roughness and irreverence in the characters of Mother Goose and the high fantasy of Burzee. Potentially I’d really like the man who was Claus to be more like the roguish King Cole.

It’s a book that feels very Victorian, there’s no denying it. I think Baum is consciously attempting to write a long-form European-style fairy tale, and it’s not the first time he’s tried that, either – though it’s very nearly the last. Personally, I don’t really have trouble with it, though I find it more interesting as a piece of world-building than I would ever say, “This is a helluva good read.” And I’ve read any number of fantasy and science-fiction novels in that vein. Ursula K. Le Guin is pretty much the grand master of the type: brilliant world-building, highly didactic, the less said about characterization the better.

What I think I would probably offer up as counter to your argument, however, is the opinion that The Wonderful Wizard of Oz isn’t really all that different. It’s more American-flavored, and there are some moments of inventive ingenuity like the origin of the Tin Woodman and the revelation of the Emerald City as a giant charade, but by and large, it is also a didactic, rather pompous, Europeanesque fairy tale. The punning, theatrical style most Baum fans really remember him for doesn’t develop until later.

What I see in Mother Goose – and it completely surprises me coming from Baum, and doesn’t necessarily feel authentic – is a lack of interest in the very idea of fantasy or the fantastic. In Santa Claus, which should be the complete opposite, the world of fantasy and the mystical is so far from lived reality that we are untroubled by it. It’s inauthentic and flat.

…I did enjoy this book, honest!

I’ll agree with you that it may not be authentic. Baum was always a man who looked to be able to sell his work, and he may have reckoned something consciously rather “Hans Christian Andersen” in tone would sell very well. When his style does change to something…looser…it does so fast, which implies he switched gears intentionally.

The fact that Mother Goose, Santa Claus, The Wizard of Oz and (for example) Ozma of Oz are so different from each other is, in itself, very interesting.

The fact that Mother Goose, Santa Claus, The Wizard of Oz and (for example) Ozma of Oz are so different from each other is, in itself, very interesting.

Well, and as I say, a teensy bit suspicious. This isn’t a man who “grew into” a writing style – he changed styles like ladies changed hats with the season.

The Oz books feel as if they become steadily more personal creations than Mother Goose or Santa Claus, which seem studiedly – oh, what’s the word I want to use? Commercial? They are stories which practically sell themselves from the title on! I don’t believe at all that he was sincere about the ideology of Mother Goose – and the Great Ak fascinates me a great deal. He feels very much a figure of the time – a Pan figure, almost. (Not as far as Michael Hague is concerned, though.)

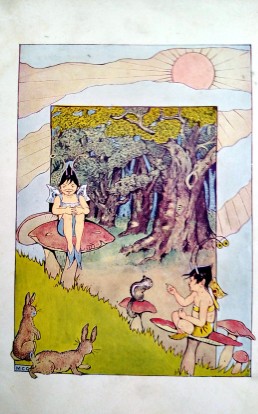

I think you’re touching on what I actually find the most interesting about The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus. Hint: it’s not Santa. The best parts, for me, are when Baum allows his imagination to run riot a little instead of just problem-solving. So I quite like the Forest of Burzee, the Nymphs, the Ryls, the Knooks, the Great Ak, and especially the big Council at the end of the story. None of those things are part of the established Santa Claus lore. It’s pure Baum. And I’d love to know how he even came up with the idea, for instance, that the world is governed by three figures who control…I believe it’s the farms, the woods, and the seas, yes? Three areas of industry.

I think you’re touching on what I actually find the most interesting about The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus. Hint: it’s not Santa. The best parts, for me, are when Baum allows his imagination to run riot a little instead of just problem-solving. So I quite like the Forest of Burzee, the Nymphs, the Ryls, the Knooks, the Great Ak, and especially the big Council at the end of the story. None of those things are part of the established Santa Claus lore. It’s pure Baum. And I’d love to know how he even came up with the idea, for instance, that the world is governed by three figures who control…I believe it’s the farms, the woods, and the seas, yes? Three areas of industry.

Then, of course, there’s one chap we’ll meet again, in a pretty big way – or perhaps it’s one of his children who rules the (G)Nomes by Ozma’s time.

I loved the names for all the invented creatures. Baum is genuinely inspired by the idea of other orders of being – fairy, goblin, pixie, (g)nome – which is a lot more of a Victorian preoccupation than that of the people who first told those old European ‘fairy’ tales, which tend not to feature fairies much at all. I mean, the odd folk tale will feature a goblin or fairy who tricks the hero, but they might as well be a devil or somebody from the tribe who lives in the next forest.

It’s very of its time. Spiritualism and the elements, etc. Baum’s little world of immortals – IMMORTALS! – like something out of Marvel Comics. And I’m fairly sure this is the only Baum fantasy to mention either Heaven or the afterlife. I think. Perhaps.

Yes! What we’re talking about is also a feature of certain aspects of Christianity, of course – the orders of the cherubim and so on. Baum is working out how all these magical beings rub along, what the rules are, when they argue what they do about it. He doesn’t go very far down this path and have a magical being philosophise about not being human – about wanting to think rationally or love a human girl or overcome their fears.

So is this the same world as Oz? What do you think? It might not be. Perhaps the better question is this: is this our world’s Santa Claus?

The only Father Christmas I can truly bring myself to believe in is the one depicted by Raymond Briggs. And I can just about believe that someone who was having a great time as an immortal in the early days of creation would also be a bit fed up of things by 1975. So, by my logic, I could say yes.

The things I really didn’t like about the book were the idea of Claus inventing the first toy and the first Christmas tree. There’s a neatness and homogeneity to that – as much as it makes Claus the originator of children’s play, a bit like Orpheus and poetry, and therefore very much one of Baum’s household gods – which makes me reject the whole thing, lock stock and bauble.

Is this pre-Oz for you? Is it part of the pre-history of that world or something separate?

I think I loosely subscribe to the idea that Something Happened. Much as we are told that Ozma descends from Zurline/Lurline, the Fairies seem to have departed…somewhere…or at least sequestered themselves. Burzee is still a functional place in Queen Zixi of Ix, but the Fairies no longer seem to be in charge of very much at all, and the Great Ak is nowhere in evidence.

It certainly seems as if Ozma is, if not The Last Fairy, at least the only fairy in Oz. And their magic – I seem to remember — is carefully distinguished from witches’ magic and conjuring. Conversely, though, the mantle of immortality that is such a big deal in the age of Ak and Co. appears to have been bestowed on every man, woman and puppy in the land of Oz, which suggests either a slipping in standards or perhaps a degree of difference in worlds between that and this.

That’s Lurline’s doing, though. It’s actually explained in one of the last Baum Oz books, and it’s not an enormous stretch to pin it down to the period shortly before or after Glinda cut Oz off from the outside world. Perhaps it put the Fairies into self-imposed exile.

It seems a shame that we never meet Mrs Claus. Santa, Ozma, Glinda and even Ak (to list them in terms of increasing divinity) seem essentially lonely figures. Or rather, solitary figures – as none of them seem to mind their situations very much. The whole land of Oz is happy in isolation. Santa is happy to basically exist as a story, a visitor at night.

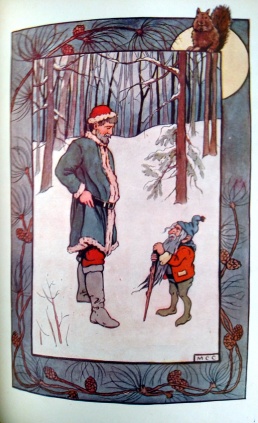

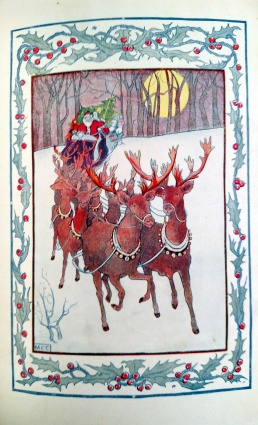

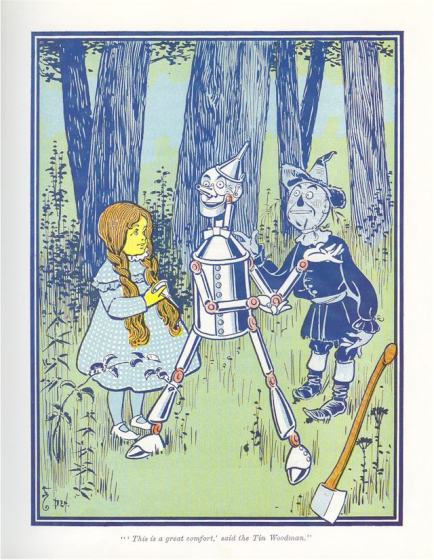

We’re back to the idea of story, and so I have to ask: how did your edition of the book affect your read? I’ve got the original 1902 book here, and it’s lovely, but the layout and especially the illustrations by Mary Cowles Clark just cement it as very, very Victorian indeed. I find myself curious if a more modern edition influences things at all.

Well, mine has pictures by Michael Hague: not in Arthur Rackham mode. He’s brighter and prettier than ever! He has lots of fun with the various gremlins and such, and there’s one particularly fab picture of Santa Claus realising he’s alive when he expects to be otherwise. It’s very respectful of the dignity that Baum gives all of his characters. Nobility, even. Claus, the fairies and Ak are all depicted as the serious figures Baum wishes them to be. Ak himself, with his beard and white wings, is even more celestially noble than I imagined from Baum’s text.

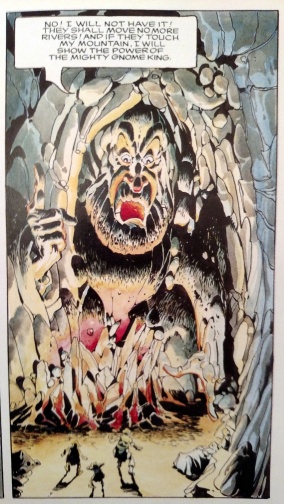

For Clark, he’s just a tall guy with a beard, which is totally underwhelming. In Rankin/Bass he looks something like an aged Herne the Hunter! And as far as books go, there are some other nice editions out there. Charles Santore did an equally reverent – and quite lush – storybook abridgment, while Mike Ploog turned the story into a graphic novel. His adaptation explicitly sets it in Oz, or near Oz, because the whole thing is framed with a visit to the Gnome King – who appears as a face emerging from the side of his mountain, as per Return to Oz (for which Ploog drew concept art). They’re both nice, but particularly with Santore’s deletion of such elements as the Awgwas, they do show up the relative frailty of the actual story. The more closely you render the plot, the more it becomes pure explanation. Ploog actually rewrites whole chunks of event, and it’s impossible not to conclude he thought that might make it – well – more entertaining.

For Clark, he’s just a tall guy with a beard, which is totally underwhelming. In Rankin/Bass he looks something like an aged Herne the Hunter! And as far as books go, there are some other nice editions out there. Charles Santore did an equally reverent – and quite lush – storybook abridgment, while Mike Ploog turned the story into a graphic novel. His adaptation explicitly sets it in Oz, or near Oz, because the whole thing is framed with a visit to the Gnome King – who appears as a face emerging from the side of his mountain, as per Return to Oz (for which Ploog drew concept art). They’re both nice, but particularly with Santore’s deletion of such elements as the Awgwas, they do show up the relative frailty of the actual story. The more closely you render the plot, the more it becomes pure explanation. Ploog actually rewrites whole chunks of event, and it’s impossible not to conclude he thought that might make it – well – more entertaining.

I’d like to think that later in his career, Baum himself might have treated Claus, those absolutely sickening children, and the dastardly Awgwas a touch more playfully. I’d just like Claus to be a little saltier. Just a little. Someone who enjoys the tot of brandy we leave out for him and depends on the carrots we leave for his reindeer…

Where to next, then, Nick? Do we jump back in time and make our way to Oz?

To Oz. We’re off to see the Wizard!

Next Time

THE WONDERFUL WIZARD OF OZ

THE WONDERFUL WIZARD OF OZ

Read along with us and send in your thoughts! Tell us what topics we should discuss! Be a part of BURZEE!

All illustration images are photographed from the book collections of Nick Campbell and Sarah K. Crotzer, are used without financial gain as examples of the original publications, and remain the property of their original creators. Please don’t steal them; go buy their books instead.

My memories of this one are vague, and I’m pretty sure I didn’t read it until fifth or sixth grade, long after the point of Santa Claus belief. It is a more austere fairy world, I do remember that; I think I liked it more as a piece of backstory than as a book to actually read. I’d be curious to reread it now that I have more familiarity with Victorian children’s literature, some 20 years later– there’s probably a whole new reading I’d have now!

My edition was a cheap 1980s New American Library paperback; I’d have to pull it out again, but I don’t think it was very visually impressive.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Steve,

Sorry not to have replied sooner – the blog took a slight pause when life got in the way. But thanks for reading and commenting. I wonder how Santa Claus reads in the context of other Victorian children’s lit – it seems unlike anything else I know of that era.

We’ll be talking about the Wonderful Wizard later this week – look out for it!

All the best,

Nick

LikeLike